HAL 9000 & Chess

Breaking down the misconception that HAL cheated at chess in ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’

Originally published on Cohost.org, November 18th, 2022

Hello. This was originally written as a three-part comment I made on a Reddit post sent to me by a friend last month. It became clear to me that nobody was ever going to read it there, sitting below 19 other responses with higher engagement, so I’ve edited it somewhat to be more suitable for re-posting here and added one new thought at the very end. (I’ve also deleted the old Reddit comments in order to let everyone who ends up there continue to be confused, so as to balance out my futile efforts in thrashing against the great confusion of word.)

I think I will probably do more re-posting like this. I have enjoyed writing a lot of similarly excessive things in comments sections and other useless places in the past. In the spirit of blogging, I think this is a better place for them. So, here is the robot chess post:

[If you trust me to get right into it, you can skip Part 2, the long part.]

. . .

Unfortunately, no, HAL does not cheat at chess in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Having seen this misconception spread all over the internet with little coherent refutation, I feel obligated to make a clarifying post for the benefit of anyone who, like me, might seek confirmation of what seems to be a neat fact. I know it is classically not fun to be explained-to about chess, and I recognize that I’m being a party pooper here, so I will try to make this as interesting, readable, and comprehensive as possible. Also, in the end, I will make an argument that something even more compelling and spooky is happening in the chess game between HAL and Frank! Never let it be said that I would defend the HAL 9000 from criticism.

First, some resources, if you want to read up / follow along yourself:

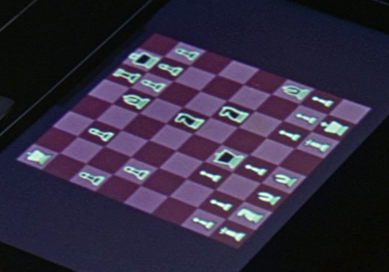

- The scene in question from 2001 wherein Frank loses a game of chess to HAL

- Reddit post on the subject where I originally posted this whole thing

- #1 Chess YouTuber agadmator’s breakdown of the original source game

- Wikipedia page about the game in the movie (note for later that this page arguably erroneously states that “...the move which HAL suggests Frank might make is not forced.”)

- Chessgames.com page for Roesch vs Willi Schlage 1910, the source game, so you can step through the endgame moves yourself and follow along

- Dead link to a SyFy.com article which doesn’t exist anymore and doesn’t seem to have been archived anywhere

Part 1: The Short Version

The idea that HAL cheats at chess against Frank is a misunderstanding arising from some admittedly not-well-explained chess factoids about how Stanley Kubrick wrote a line of chess notation incorrectly in the script, which made it into the film (true). Misinterpretation and fan-theory speculation over this minor error has compounded and spread by anecdote across Stack Exchange, Reddit, Chess.com, YouTube, and elsewhere. As the reddit OP linked at the top points out, it does indeed seem to stem from a SyFy article from some years ago, which they have since deleted (probably because they learned it was incorrect). In the film, the game HAL and Frank play out is a real and legitimate one from recorded chess history (Roesch vs Willi Schlage, 1910), with no cheating involved, and HAL correctly identifies the moment when Frank commits an error which makes HAL’s victory inevitable by one of three paths. HAL’s error in describing one move could not reasonably be construed as misleading Frank, because the erroneous description taken literally would be nonsensical, impossible, and does not assist in any kind of checkmate threat. Furthermore, Frank indicates that he understands he has lost, which he has. It is possible for Frank to delay the checkmate longer than HAL describes, but only by one move, and Frank would still lose.

Part 2: The Long Version

The endgame of Roesch vs Schlage, as shown in the movie, has the potential for a legitimate forced mate (from the moment of 15. ...Qf3 onward) in one more turn via a couple different paths, or in three turns by another path, depending on how long white fights back. The one-move mates are 16. ...Nh3# (if, for some reason, Frank makes another move without taking the queen), which agadmator describes in the above linked video, or 16. ...Nxf3#, which HAL describes as the inevitable response to Frank taking the queen. The Wikipedia entry on this game for some reason describes a possible prolonged four-move mate where Frank could attempt to stall, as follows: 16.Qc8 Rxc8 17.h3 Nxh3+ 18.Kh2 Ng4# ...However, since the queen and rook activity in this proposed line is irrelevant (Frank’s potential 16.Qc8 is not a real threat, and it isn’t necessary for HAL to bother taking Frank’s queen on c8 when 16. ...Nh3# still wins the game immediately), it would be more accurate to say this could be played as a three-move forced mate where Frank uses h3 to prolong the game by one move further.

It may help to note here that there seems to be some colloquial variation of what “forced” actually means in chess language; You could use the terms relative and absolute to describe this difference of understanding (these are already-existing chess terms for discussing pins). A move is forced in the absolute sense when there is no other legal move possible for that player to make, e.g. when the king in check must move to only one available square. A series of such moves that leads to checkmate is a “forced checkmate” in an absolute sense. On the other hand, a move is forced in the relative sense when the player does still have other legal options, but they must play that move or else they will certainly be checkmated. A series of such moves that leads to checkmate is also known as a “forced checkmate” or “forced mate” in the relative sense. Furthermore, people even use the term “forced move” to describe a move that must be made lest that player suffer a serious disadvantage―not necessarily one even immediately related to checkmate. This is a mess. The point, however, is that when someone says “the move which HAL suggests Frank might make is not forced,” (as is written on Wikipedia) this is technically true in one sense of the term, but it is incorrect to read and surmise that Frank had viable options for survival, and downright false to make that implication.

Case in point: Roesch resigned in the 1910 game just as Frank did. He had already lost, and he knew it. The two players probably had a short discussion similar to the one we see in the film.

It is important to point out that HAL goes on to describe the path to checkmate which involves Frank continuing to resist the attack. Central to the “HAL cheats” thesis is an oft repeated notion that HAL is deceptively telling Frank he must resign without mentioning that Frank could keep fighting. It’s true that Frank could play 16.h3 for the three-move prolonged mate as we saw above, but Frank still loses in that line, and neglecting to mention another way Frank could lose doesn’t really count as cheating―plus, h3 isn’t even the move people seem to be calling for in these anecdotes. It’s usually just that they’ve combined the fact of the notation error with the unspecified possibility of further moves.

In fact, the reverse of this supposed deception is true. In HAL’s [irrelevantly misspoken] accounting, it is implied and apparent to both players that there is an immediate checkmate threat once the queen defends the bishop with 15. ...Qf3, and HAL continues further to tell Frank what will happen if he keeps playing by making the only reasonable and most obvious move available (taking HAL’s Queen which he intends to move into a sacrifice position). Frank seems to understand, and he resigns. But it doesn’t really matter whether Frank understands or not. His last move with the rook was a critical error, and he is going to lose no matter what.

So, about the notation. This misconception about cheating has arisen from a minor error in HAL’s descriptive notation of his queen move within the aforementioned endgame sequence. What is descriptive notation? To be brief, descriptive notation is an old-style way of identifying chess moves, before it became predominant to use modern algebraic notation. In descriptive notation, the moves are called according to each player’s own perspective and according to the starting position of the back-rank pieces. For example, “Queen to king three” or “queen to king’s third,” etc., means “I move my queen to the third square in the file where my king started.” If this seems to you like it might have some problematics which would need to be clarified, you’re right―that’s pretty much why people switched to algebraic notation. Anyway, the key point is that you always speak a move from your own perspective in descriptive notation. HAL and Frank are using a combination of descriptive notation and natural language, where you would say something like “Queen takes pawn,” and contextually it’s just obvious what you mean.

The error that HAL makes in saying “queen to bishop three” has basically no effect on anything. I can’t say for sure how easy it would be for an avid chess player like Kubrick to write such a mistake, mistakenly, as a chess player at the time, having never myself used descriptive notation (which, again, Kubrick would be very familiar with), but if you actually look at what’s on the board, it’s hard to see it as anything other than a totally innocuous and unsurprising slip. If, as I have heard reported, Kubrick did indeed say in some documentary, (or others said secondhand in their own recounting what he supposedly said?), that the mistake was intentional foreshadowing... idk, I think either those people are misquoting him or mythologizing, or he was mythologizing himself (i.e. bullshitting) and dressing up his mistake. It is mundanely quite likely that Kubrick simply forgot to have HAL speak from his own POV opposite Frank’s, an easy mistake to make (despite, yes, his familiarity with the language), because notably: Kubrick is not HAL, and Kubrick is not Frank. He’s writing from imagined perspectives in the first place, and he also wants us to the see the film from the humans’ point of view. Regardless, it is clear that Frank understands the forced mate HAL is indicating, and even if he were to take HAL excessively literally, there’s no way you could call that cheating because the move HAL literally describes doesn’t make any sense.

To put it another way, for HAL’s verbal error to be considered cheating, you would have to believe that Frank saw an utterly nonsensical impossible move that HAL would never and could never make (but described) as somehow a checkmate threat or even a legitimate move of any kind.

NOTE: There is also some conflation of this mistake, in these various anecdotes on the subject, with a “mistake” HAL makes with his moves earlier in the game. This is simply a matter of it being a real game played by humans in 1910, and some of Schlage’s/HAL’s moves have since, of course, been deemed less than 100% perfect. Schlage at times played moves that a current-day chess computer would consider to be “sub-optimal.” That’s just the best they could do for this film at the time (Deep Blue was only getting started and I guess not available to Kubrick), and that level of analysis is probably not even something Kubrick would be deeply aware of for every move in this random game. Don’t read into it too much.

TO SUMMARIZE: HAL has found a path to inevitable victory, he knows he has already won, he describes to Frank how he will win no matter what, Frank expresses that he understands what HAL is describing despite an irrelevant error in HAL’s language, and so Frank resigns. Again, HAL’s victory was inevitable at that point. He did not push Frank to resign where Frank could have still turned the game around. Frank was going to lose. It was already over.

As a last note on the subject of HAL [not] cheating, and deviating a bit from the strict chess analysis back into the fiction, I want to additionally assert that HAL would never cheat at chess against one of his human crewmates, because he cannot be certain they won’t catch him! Disturbingly, that’s probably the only reason he won’t cheat at chess. If he could assuredly get away with it, and it mattered, he might do it. But the probability of them catching him at such an act seems pretty high. Even if he were to try and cover with something like “Good job, Frank, I was testing you. This has a been a successful chess exercise :-) ” the incident would have revealed that HAL is capable of being dishonest with them. That would be disastrous for HAL and his hidden capacity on the mission. So why would he risk it over a game? He wouldn’t. He’s literally too nefarious to cheat. Which brings us to...

Part 3: The Fun Part

In the novelization of this story, which Arthur C. Clarke wrote concurrently with the screenplay, it says that HAL is programmed to let them win 50% of the time in the service of human morale: For relaxation he (Dave Bowman) could always engage Hal in a large number of semimathematical games, including checkers, chess, and polyominoes. If Hal went all out, he could win any one of them; but that would be bad for morale. So he had been programmed to win only fifty percent of the time, and his human partners pretended not to know this.

In other words, HAL is always in control and fundamentally not honest in that sense, which is subtly distasteful at baseline. Furthermore, however, note that Clarke also says the astronauts are aware of this, and they simply play the game as if they’re not at the whims of HAL. In this way, they are treating him as a benign form of entertainment when he is actually something much more dangerous.

That’s just in the book, though. There are no actual chess moves/positions described in the book. In the film, where we see the game, I think what is depicted is even more ominous than cheating and very specifically foreshadows the most dire events to come: Frank lets his guard down, and HAL strikes, dooming him. If you imagine that Frank is represented by the most active white piece we’ve seen, the queen, the piece with the most agency, it is even more clear that he is helpless. HAL then describes to him logically how and why he must perish. Remember also that HAL describes the slightly longer path to checkmate, essentially what will happen if Frank puts up a fight. He is basically saying: “DO NOT RESIST.”

Later, after Frank is dead, this is more or less what Dave experiences, too. He gets locked out of the ship (locked out of the game) while HAL does what he wants. It’s HAL’s board.

I think it’s also fun how HAL’s lines to Frank at the end of the game mirror his later standoff with Dave:

In the game ― “I’m sorry, Frank. I think you missed it.”

In the pod bay doors scene ― “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can't do that.”

HAL uses the word “sorry” a few other times in the movie, but in general he seems to say “sorry” when he is either withholding information or exerting control over a situation. I think this is a really nice and spooky theme.

Why is it fun to believe that HAL cheats at chess? I sincerely apologize for posing such a radiolab-ass fake science-of-the-mind type question and the presumptuous speculation that it invites, but I think it’s interesting, and I will try to keep it shallow. I think there are basically three answers: The auteur element, the chess element, and the science fiction / AI element. The auteur angle is just that we have this preexisting expectation that the renowned creator of the film was super clever and thus it’s believable that he snuck in this thing you’d never really notice, just because he could, and it’s neat, and that’s film, mind blown etc. I have no problem taking a jab at this mindset, and I’m not interested in getting into it any further. The chess angle is even more superficial. It’s fun to hear what sounds like a chess factoid, because chess is understood to be a smart people thing, and if you understand the factoid without understanding its actual mechanics, you feel like you got a bit of the smart thing under your belt. I don’t mean this to sound belittling; trust me, I am likewise a person who revels in shallow chess factoids, and I’m not very good at chess.

The science fiction / AI angle is kind of disturbing. It is exciting for us, posters and readers of posts, to hear this fun fact about a story where a constructed intelligence is able to become smart enough to figure out how to cheat the humans―equating intelligence or free will, for better or for worse, with the ability to be deceptive and disobey orders―in a way that we believe we understand at a glance, because it offers a secure place to stand. We know what the machine did wrong, and we know why it did it, and we understand that if we had just played better chess, we might have won. No: the chess game is already lost, when AI is concerned. You can’t beat the machines at chess, and they don’t have to cheat, and they’re beating you on a level you don’t even understand. They’re not playing chess.

Anyway, great movie. Don’t trust AI. Play chess, or don’t play chess.

Peace