Let's Talk About Chi Chi Chess

A look back at an obscure chess fad of 1968

Originally published on Cohost.org, April 5th, 2024

A while back, looking through D. B. Pritchard and John Beasley’s Encyclopedia of Chess Variants, Second Edition [PDF], I came across an entry that grabbed my attention.

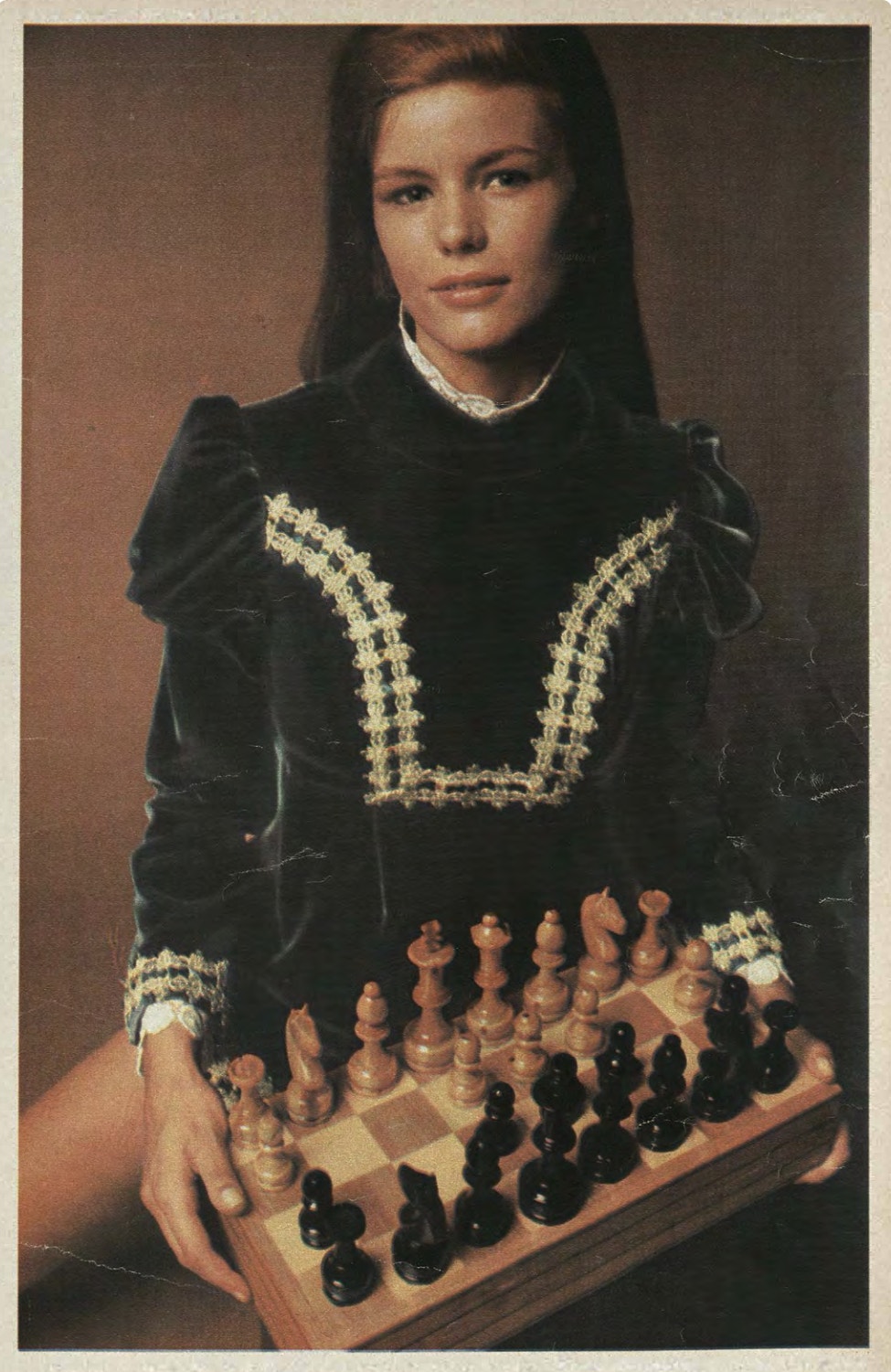

“Chi Chi’s Chess (Chi Chi Hackenberg, 1968). The exposure this variant received in Eye (November 1968) had much to do with the charming inventor (photo by John Ford, dress by Eloise Curtis) and little to do with the charmless game. Board 8x4; normal baseline, pawns on a/c/d/e/h files only, pawns can move (straight) and capture (diagonally) backwards, and White cannot move a pawn on the first turn. Even so, he [sic] has a forced win.”

This sounded like there was a story to be told, and it also seemed... you know, rude. And strangely narrow-minded. I don’t know whether to blame Pritchard or Beasley, but they’ve put together a gigantic collection of chess games for weirdos and chose to single out just one as charmless? (Not that I’ve read the whole thing.)

You know I had to find out what’s up with Chi Chi Chess.

Chess variants can be many things to many different people. First and foremost, a chess variant is simply chess but from a prior historical state or an attempted future; the endeavor of making slight changes and additions to clean the slate of opening theory, to renew the mystery of the game. The mirror inverse of this focus is the desire for more of what it already is, but without the restraint of iterative change, not to change the game to make it last but rather to change the game in pursuit of an accelerating strategic craving, chasing the ever-heightening intensification of complexity and conflict, the dueling nature of the one-on-one game, the contest of wills, the meeting of minds. These often focus on the associated military themes and sometimes use that as a guide for their tinkerings. More creative and experimentally oriented versions of this impulse will add twists to things like turn order, grid shape, the determination of endings, etc., and from that point of departure, we venture into the world of pieces with special powers, rulesets deep with esoteric tricks, and other attempts to draw out the feeling that playing chess is a way of doing cool wizard stuff. Many variant designers focus on the medieval associations of chess and create new pieces with fantasy themes, magic and mythological creatures. It’s all either fun or insane, a pastime or an adrenaline fix. There is no consensus on the point of it, but there are undercurrents.

The sudden discovery of an intriguing position, the possibility of romantic stunts, the pursuit of chaos in harmony, harmony in chaos, seeking meaning in myriads, these are the ineffable poetries that all call out to the chess variant enthusiast. And even this is not a complete or systematic way to describe the variety; the variety is variously various.

But I have a bias, obviously. For me, chess is simply some moving parts comprising a kind of alchemy of grids. It’s a language, it does whatever you want.

Before requesting a scan from my local library of the original article (for the picture above), a quick search turned up an archived diary entry held by the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY. The writer of the diary, one Sid Sackson, a game designer of note, copied down the aforementioned Eye article in full, which includes the rules of Chi Chi Chess:

“Just fold the board in half. Then each player sets his pieces as usual, except for removing three pawns (see picture). There are only two new rules. First, white cannot move a pawn on his opening move. Second, pawns can go backward as well as forward—one step straight back into empty squares, diagonally back when capturing. A model of simplicity, her rules are designed to enable the players to plunge immediately into the middle game (eliminating the usual, slow-moving prologue)”

I personally think that the focus on simplification and skipping the opening does not give a complete picture of the value of Chi Chi Chess. More on that in a minute. But the appeal of the game’s immediacy is very clear.

Here’s where my research kind of breaks down... I went through a lot of this in a frenzy and later forgot where I learned it. But, so, back in the 1960s there was this correspondence chess mail club called kNights of the Square Table (NOST). They played a lot of chess variants, and I read somewhere that they had a sort of Chi Chi Chess craze for a minute until two players solved the game for white. Somewhere else in my digging related to this, I found another diary entry that started something like “Played more Chi Chi chess today...” This is all very much 2:12 AM going back for more olive energy to me.

So the story seems to be that Chi Chi’s chess variant, in the larger context of the supercharged Cold War chess sphere of the 60s, became a sort of micro fad in some part of New York, where she was a student. Word got around, and she was featured in a short-lived music and culture magazine. The game blew up in the small world of 60s chess variant enthusiasts—then it was solved, and they dropped it.

It’s frustrating to see this story relegated to a dismissive and belittling entry in Pritchard’s Encyclopedia. There is, frankly, some misogyny in the tone and the implication that the interest sparked in the game was totally superficial. Is it kind of silly to do a fashion shoot over a chess variant? Maybe, but A) that’s magazines, and B) that’s largely out of Chi Chi’s hands, isn’t it? She likely did not even choose the dress. Her inability and non-obligation to control how people are going to perceive her extends from the photoshoot on into the penning of your book, ...and furthermore C) who cares, guys? What about the chess? Is there perhaps more to say beyond that the game was solved and should be dropped forever?

There is, in fact, a whole tradition of designing “minichess” variants on smaller boards with condensed piece sets, and in a variety of board configurations. First, these games attempt to distill standard Western chess into the least number of units possible, including spatial units, and then make adjustments to arrangement of pieces on the back ranks and to the length of the board in order to accommodate openings and pawn interactions. The way I see it, the length and width of the board do different things. The length of the board adds complexity and duration to the incrementally developed steps of opening. The width of the playable field does a bit of the same, but due to the lateral arrangement of pieces, it also adds more immediately available, more broad and diverse geometry to the possible moves one can make.

Chi Chi chess makes a very distinct choice with these dimensions. The breadth of play available in the standard set of pieces remains, but the length of the field is the length of right now.

The reason I love this is, admittedly, selfish. When I was in the early scrawlings of my own game idea (which eventually became a chess variant), what I initially envisioned was some kind of physical device with interlocking moving parts. These parts would be controlled by different players and slide around like a puzzle box, their movements sort of analogous to the pieces on a chess board. Players take turns making discrete movements until one succeeds in forcing the configuration that corresponds to a win. I forgot about this as soon as I switched to chess and went to town with 1,000,000 different new chess moves, but here it is, Chi Chi went and did it: The toyification of chess. Pawns being able to move and capture forward and backward is crucial here. Chi Chi’s vision was a chess that uses the pieces as moving parts in a machine where they interact directly and immediately. This game now works like two people trying to pick the same lock, fighting to make it open to a reality in their favor.

It’s also a bit Mensur to me, unfortunately, that is to say the cursed olde fraternity sport of German Academic Fencing, wherein combatants stand straight in front of one another with actual blades and aim for the head.

The article in Eye says that Chi Chi “devises chess problems for relaxation.” That may be true, but in the statement’s adjacency to the subject of Chi Chi Chess, I think that relaxation is, if colloquially apt, probably not exactly the right idea. Pastime, passion, “for fun,” whatever. Maybe chess is relaxing for her, maybe it’s thrilling. Chi Chi Chess seems to be going for approximately the same thing that minichess variants attempt: The struggle to simplify and distill the game down to a version with maximal activity with the least number of parts. This is sort of a conflicted passion, in that there is obviously a lower limit where the game becomes solved. One wants the most from this thing that they try to reduce into something more immediate and pure.

So, naturally, all these chess variant fiends in the mail club got their hit and then moved on to the next craze or back to their old standbys.

What’s the most popular minichess-like thing today? Probably Minitchess? Seems cool, but this is far from a settled area of interest. I think the focus on using only King, Queen, Knight, Bishop, Rook, and Pawn is slightly misguided, although they are (ignoring pawns) geometric fundamentals; MinitChess takes a nice step in the right direction by giving the Bishop one-square orthogonal moves to change square color (not by capturing).

Somewhere out there is some kind of new chess widget that could crack this thing wide open―pieces suited to their board, and a board suited to their pieces.

Chi Chi Hackenberg would be around 75-80 years old, today. Is she still out there? Is she still Chi Chi? Does she still play chess?

Does she still play weird chess?

[1.] Pritchard, David Brine. Ed. John Beasley. The Classified Encyclopedia of Chess Variants: The second edition of The Encyclopedia of Chess Variants. p.114. Originally printed in Great Britain by Biddles Ltd, King's Lynns. www.jsbeasley.co.uk/encyc/encyc.pdf. 2007. PDF. ISBN 978-0-9555168-0-1

[2.] “Speed Chess ― The Name of This Game Is Chi Chi,” Eye, November, 1968, Vol. 1 No. 9, p.67.

About the dress:

Forum user denisebrain says:

“Eloise Curtis appears to have been a young designer in the mid to late 1960s. This is from the Bridgeport (Connecticut) Post, 1/68”

Scan reads:

“Eloise Curtis for David Styne is another young designer who uses the demure mood, the ‘little girl’ look, the ‘Gibson Girl’ and the ‘romantic’ with great success. Peter Pan collars, lingerie touches, ruching and run-through velvet ribbons all add sugar and spice to some of her very feminine crepes.”