Impromptu: Chess, Surrealism & Games

This was supposed to be for my P*treon, but trying to make the images work was so busted I'm giving up and posting it here. Enjoy!

Originally published on Cohost.org, May 11th, 2024

There’s something funny about my veney board being on display in a little gallery alongside some other beautiful objects. At first glance, to the viewer without any foreknowledge of chess variants, it probably looks strange. It’s an oblong chess board, obviously a subversion of chess of some kind, and you’d be forgiven for assuming it comes from absurdist intentions. It’s not quite as clear as if it were, say, a chess set with randomly many-hued pieces, or two completely disconnected grids, or some other twist of poetics. But it is weird, and the gallery context especially enhances a predisposition to assuming that there’s some trick to it. I am biased, I guess, as someone with a history of making extremely self-conscious submissions to art shows which play around with the gallery setting and the practice of art-as-art in general.

But it’s not just me, I’m sure. The board is on display next to a piece of metalwork which appears to be a frame for a mirror or a picture, nothing framed in it, standing upside down and backwards, leaning against the wall instead of hanging by its cord. I could be reading this wrong, but from a look at the author’s website, she has worked with picture frames as art objects in the past. There is a certain vibe in the gallery which I’m glad to be part of, is all I’m saying.

…The funny part, to me, is that if you check out my website for my weird game board, it turns out to be actually a huge list of very specific rules, not absurdist at all, really (Maybe you could argue it’s absurd, if you wanted to use that as a pejorative, but it is not absurd-ist). Sort of disappointing for anyone who may have hoped it was just a chess goof and not rules, rules, rules.

But there is a long history of artistic use of games in conjunction with absurdism and surrealism. The latter especially is important to me, and the Surrealist obsession with chess is a happy coincidence, so I thought I would talk about it a bit here. This will not be extensively researched, as usual, just thoughts and bits I remember offhand.

Above: Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp playing chess in a short film, “Entr’acte,” directed by René Clair. The scene ends with a sudden torrent of water destroying the game.

For your consideration: Surrealism

Allow me to first summarize the continuing relevance of surrealism in the world we live in today. It’s a deep subject with a vast scholarship that, again, I will not be rigorously citing here, because I am not a scholar. I simply drank coffee today.

In short: the foundation of surrealist practice across art forms and extending into social thought was a moment in history that was quickly misunderstood, watered down, commodified, dismissed across tendencies of thought and simultaneously subsumed in its less frictional modes into everyday parlance. It came to us, appropriately, like a dream; You remember profound glimpses for a few moments in the waking world, memories of some powerful and elusive truth, and then it slips away. Later, all you can remember is that there were frogs on stilts. “Must have been nothing.”

Surrealism was, and remains, a humanist movement to liberate the unconscious mind from the machinic, imprisoning, rote logic and conventionally accepted self-destructive mundanities of the world we find ourselves within, every day, unchosen, like a recurring dream we wake up into; thus the dream and the unconscious mind, the illogic of impulse, these things are given due recognition and embraced as the guiding spirits of the practice. The practice of surrealism is also a “practice” in the meditative sense. It is not a craft to be perfected, it is never finally attained, but rather a constant cultivation that is shared and lives on in living people. Surrealists aim to collectively, experimentally, and joyously train ourselves to be able (both alone in our dreams and together in waking) to see true possibility …instead of letting our minds become hammered into shape as anonymous widgets in the machine being mindlessly built around us. This is the natural inclination of artistic people in a post-WWI lineage, survivors of the first apocalyptically mechanized war in Europe. Today, in a timeline of burgeoning fascistic national movements; warmongering; engineered pipelines, and dehumanized, data-driven machine minds deciding everything around us; the ethos of surrealism is direly needed.

Above: “Endgame,” Dorothea Tanning, 1944.

Surrealism is not absurdism for absurdism’s sake (neither was Dada, its conflated predecessor, I should mention; and nor is any absurdism, arguably …just as with anything else, an action cannot be understood with such facile shorthand.) Surrealism is not edgelord-ism or intellectual prevarication. Surrealism is not a superficial aesthetic of worshipping the strange. It is mistaken for these things for the same necessity of its intended purpose, to try to teach the mind that, untaught, would misunderstand its usefulness so badly.

The tragedy is that surrealism offers a key to a lock, and the brutalized mind says “Haha! The key is shaped weird,” and walks away, lock unopened.

Surrealism in its time of origin was nothing short of a magic-realist revolutionary project; indeed, it was (and, in some secluded sectors, still is) in constant communication with other revolutionary projects around the world. For this same reason, the stupid ones (ahem, Dalí) did indeed turn to edgelord-ism, intellectual prevarication, and ultimately fascist ideals before getting kicked out of the movement. We must also acknowledge that the Great Men of surrealism back in the day had plenty of other problems, beyond just Dalí, with internalized misogyny, homophobia, and racism. Many of them learned better. Many of them published a lot of trash before learning better. They had discovered, basically, that they could just sort of say shit, and obviously they were not all readily equipped to handle that discovery with grace. So, I’m being careful here not to take the easy route of simply defining everything with citations to everyone you’re already tired of hearing about. If you’re still wary, please know that it’s not mandatory for you to study the same dudes that stuffy historians and decidedly un-surrealist managers of canons keep forcing on you. There is incredible work to be seen, read, and heard by surrealists who were not them. Check out Remedios Varo, Toyen, Federico García Lorca, Claude Cahun, Hector Hyppolite (an uncited inspiration for Breton and the rest of the movement)…

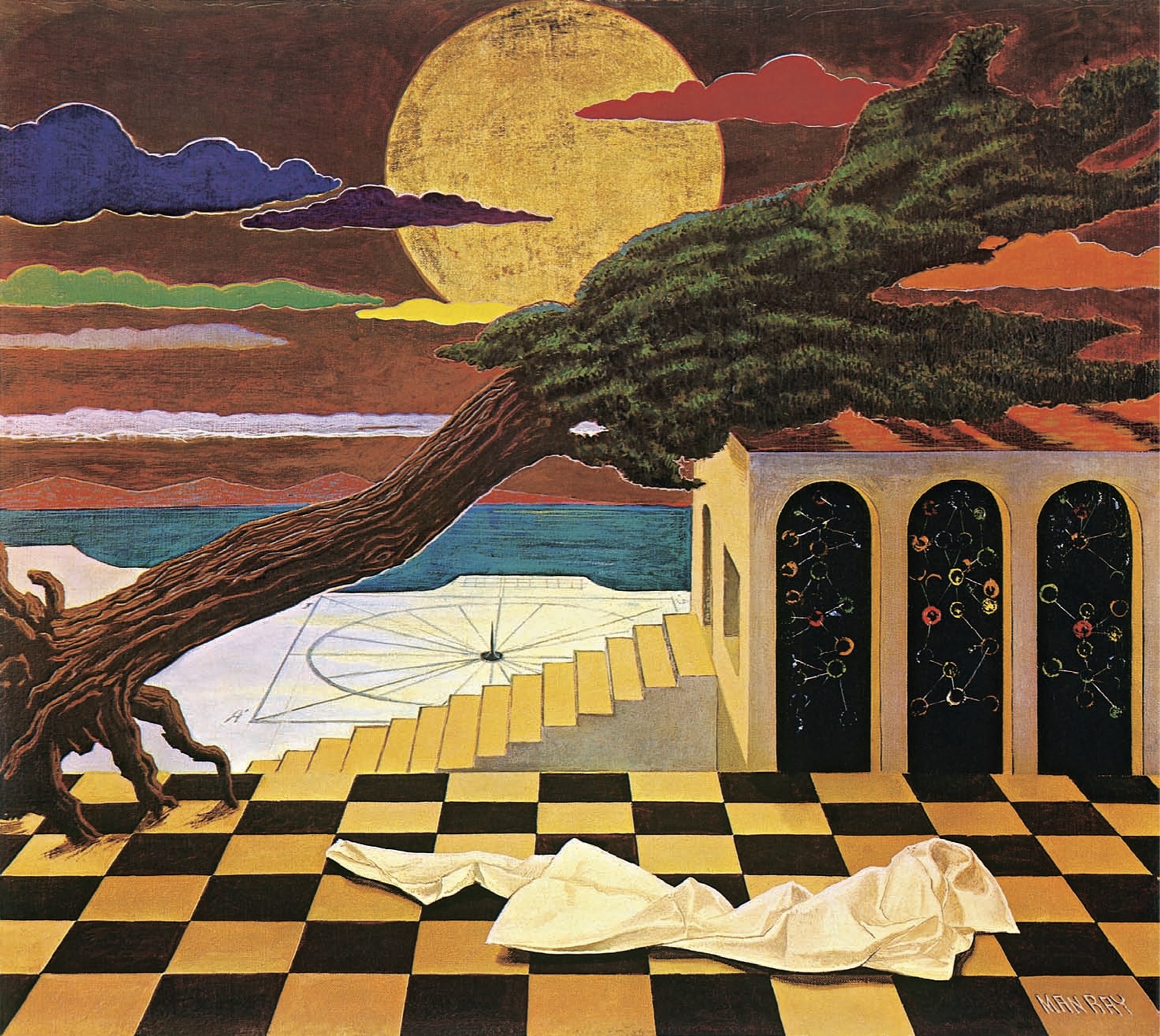

Above: “Night Sun - Abandoned Playground,” Man Ray, 1943.

Miserabilism

There is a term used a lot in surrealist thought, “miserabilism,” and the opposition to it, the investigation of tactics to disrupt it, etc.

This was already a word with a conventional definition outside of the niche of surrealism, generally meaning a pessimistic philosophy, whether conscious or unconscious, a gloomy outlook reveling in melancholy and futility. It’s worse than that, though. To surrealists, miserabilism is a hard -ism. The word is used to refer to a sort of Pavlovian mental mechanism cultivated in the mindset of an institutionalized member of the machine. Miserabilism is the habit, the comment, the joke, the daily sigh that reiterates and reenforces the same miserable state of affairs it seeks to ironically make tolerable (often via humor or sarcasm). Miserabilism is the mindset that says this sucks, lol, let’s find the easiest way not to think about what that means. It’s the “Hang In There” cat poster. It’s the jokes about cats having office jobs or PhD stress. It’s the memes where the ways we destroy ourselves are cute and funny and relatable. It gets at us, all of us, a little bit every day, because it makes everything feel slightly more okay, and we are at least not alone in our misery. But it is, or can become, miserabilist.

I’m lacking the exact source for where I originally got this, but here’s one I just found: Penelope Rosemont’s “Disobedience: The Antidote for Miserablism.” [EDIT: I’m not linking to it due to the uh current political climate.]

What’s another antidote for miserabilism? Games baby!!!! Games and toys and playing around!!!!!!!

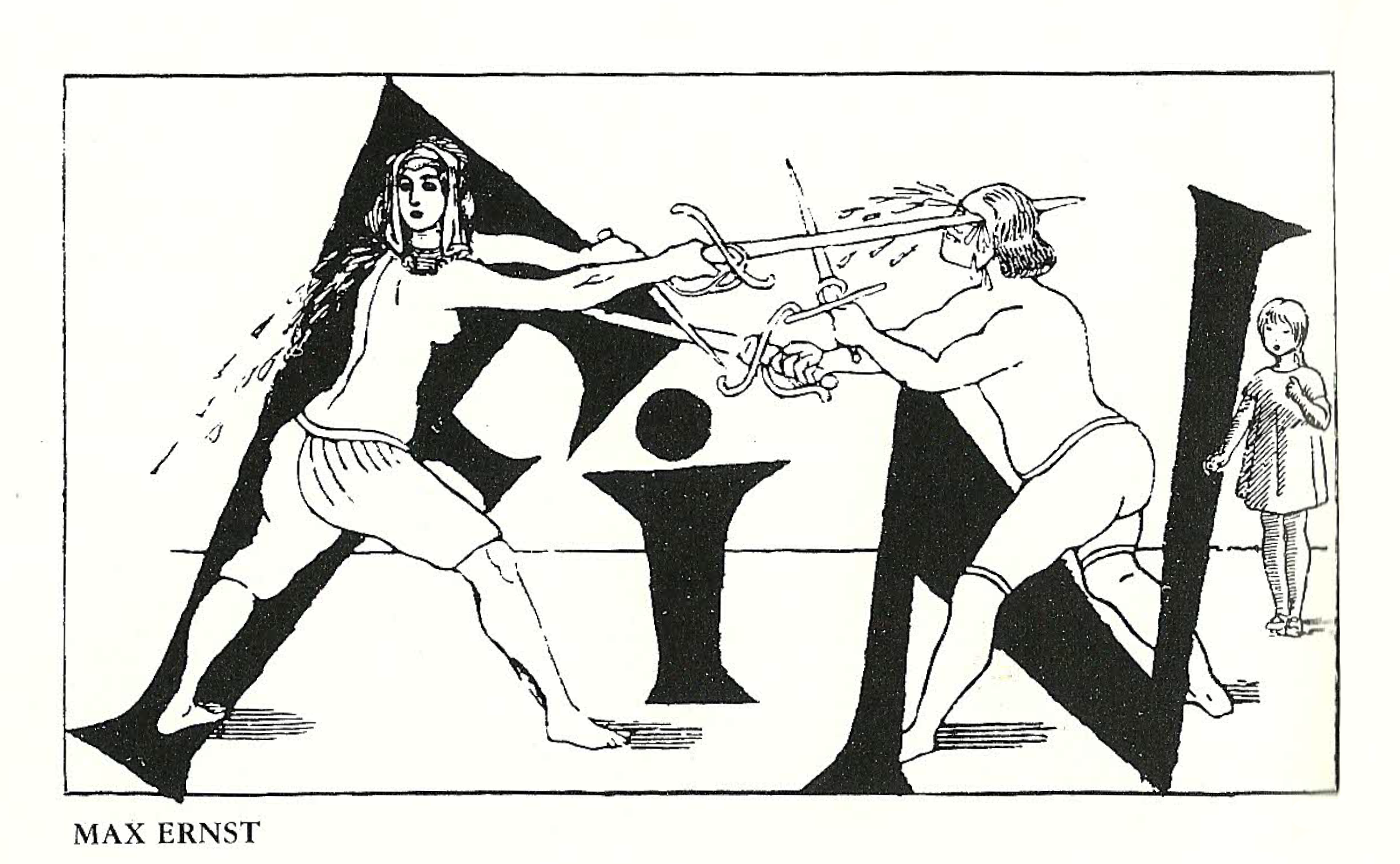

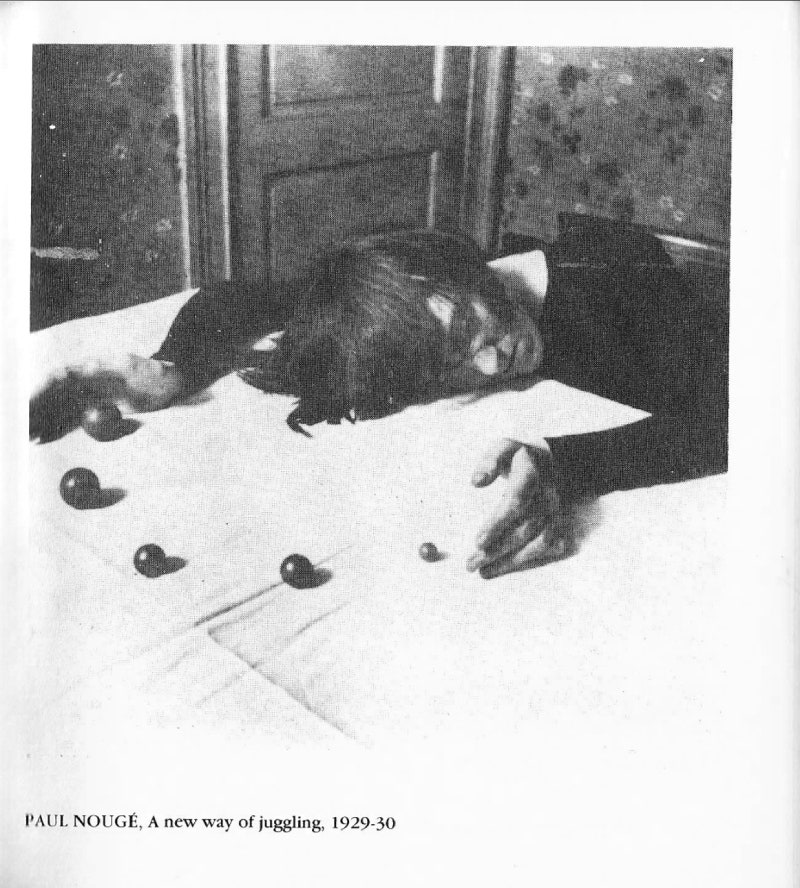

Above: Paul Nougé, “A new way of juggling,” 1929‒1930. I enjoy the accidental(?) implication that he did this for a period of time spanning from one year to the next. From “A Book of Surrealist Games,” 1995, compiled and edited by Alastair Brotchie, edited by Mel Gooding. PDF from Monoskop.org

Games!

Alright, we’ve established that we live in hell, that it hell-ifies our minds, and that we have the tools to break free latent inside us. Let’s talk about those games the Surrealists played. This is a glorified list that will devolve into disconnected thoughts, but here we go:

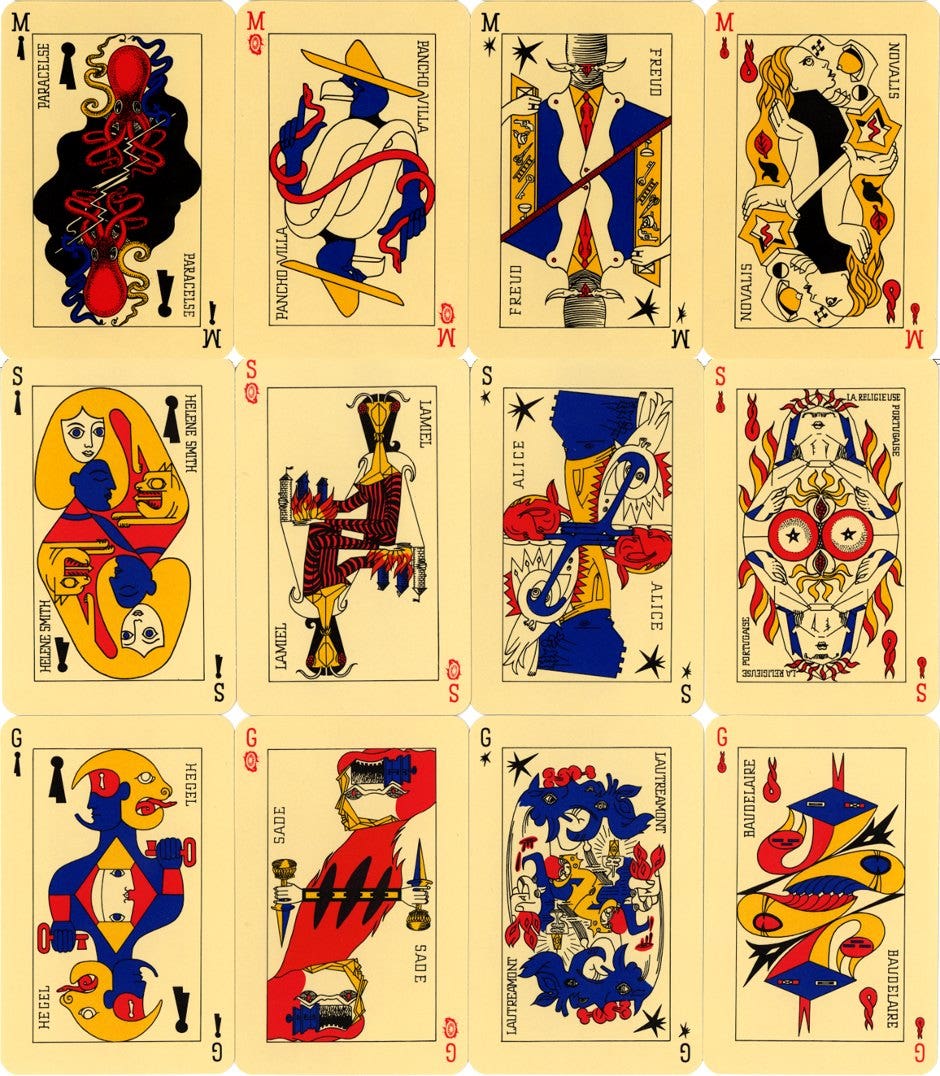

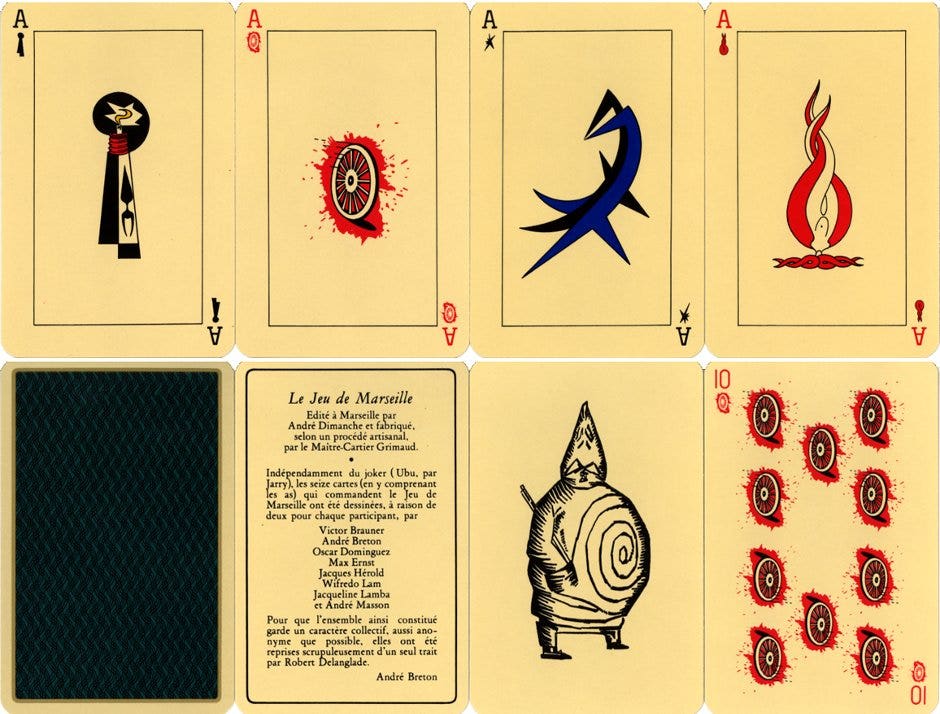

Le Jeu de Marseille - a Surrealist-designed deck of playing cards

Some of these nerds redesigned the standard deck of playing cards with no more royalty (instead, the Genius, Siren and Magus) and new suits with a surrealist theme: Locks, Stars, Wheels, and Flames. The interest in / application to Tarot, cartomancy, etc., is obvious

Le Jeu de Marseille, suits, Joker, card back, etc.

The Exquisite Corpse

A drawing or writing game. You’ve heard of it. Yadda

…and Parallel Collage

From zazie.at: “This surrealist game requires a minimum of 3 players. Each player gives 2 graphic images and 2 lines of poetic text to the other players. All players then use the images and lines of text (including their own) to construct a collage-image and collage-poem. In the process of construction, a player can modify any item, in any way desired. Until everyone is finished, each person’s work is kept hidden. When all images and poems are complete, they are shared among the players, with a comparison of the results.”

All surrealist methods of producing art have an element of playfulness, most visible in the above two collaborative examples but extending into many experimental techniques in different mediums.

Surrealist chess sets

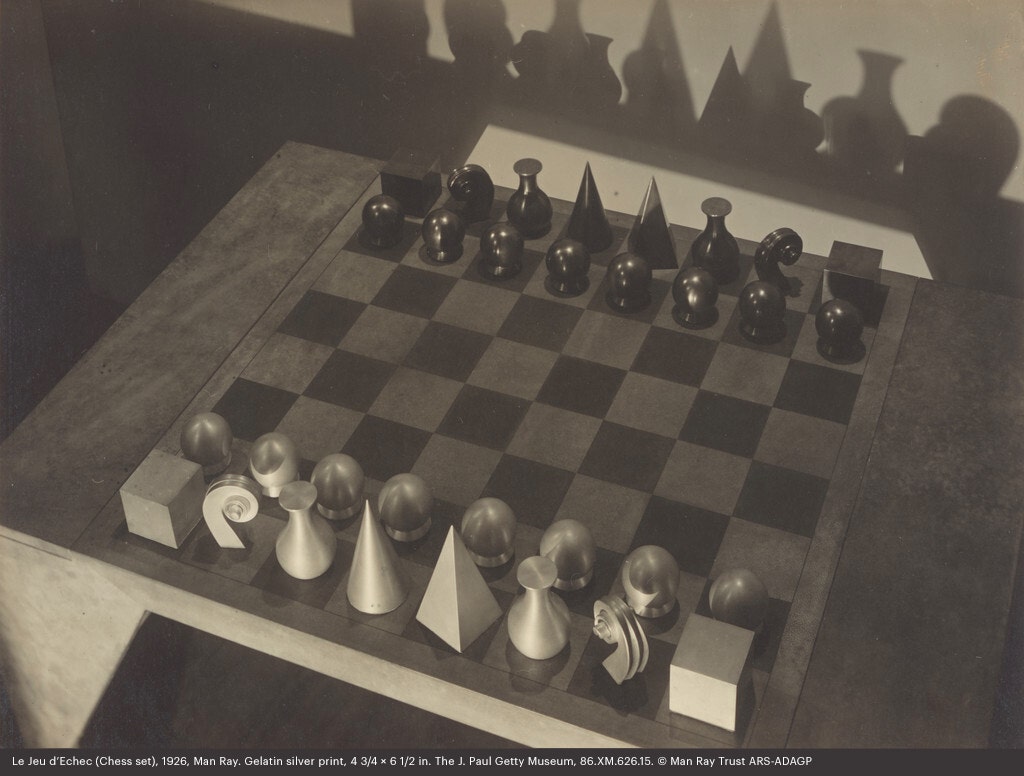

Several famous surrealists designed chess sets, most notably (imo) Man Ray, who produced this banger. Today, it can be found for sale at a price of three to seven hundred shmonies in museum gift shops and on interior design junk websites.

Chess set by Man Ray, 1920(?), photo 1926.

Above: “Permanent Attraction,” Man Ray, 1948.

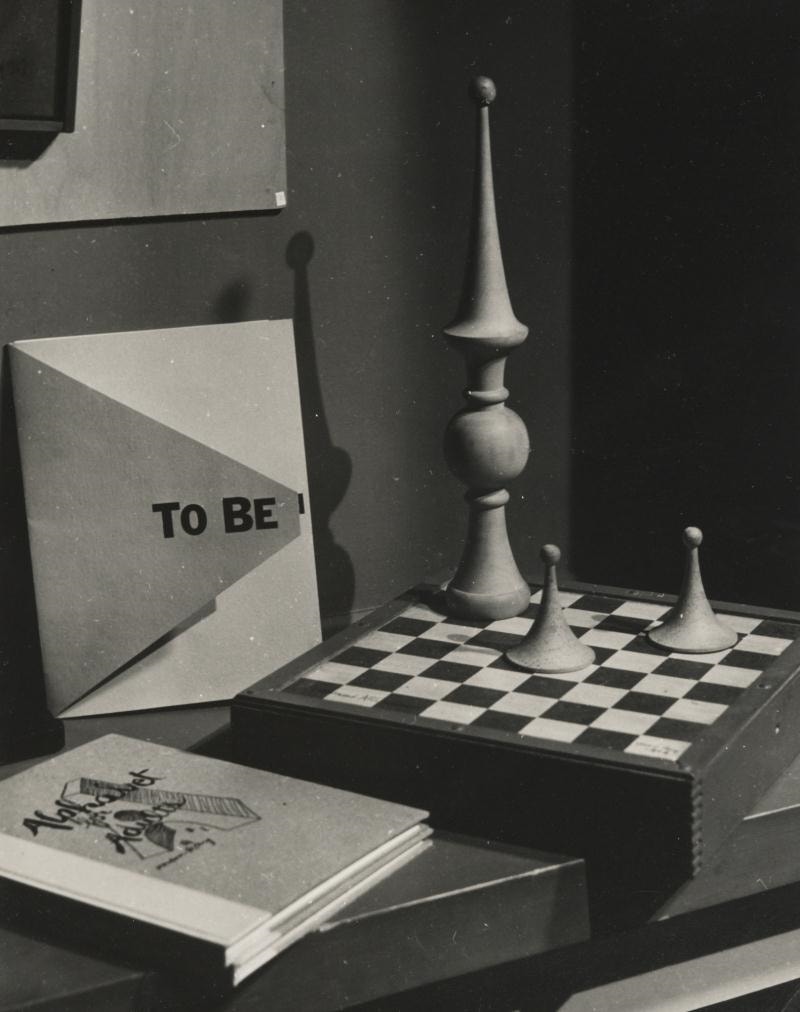

Above: Chess set by Alexander Calder, 1944. Calder was not a member of the Surrealists as far as I know, but he was certainly a fellow traveler.

Marcel Duchamp and chess

Duchamp, alongside his collaborators, laid the foundations for the work of the later European Surrealists. He also played a lot of chess. He had some involvement with the Surrealists, but was not a member. You’ll hear that he eventually more or less retired from art in order to play chess, but some will say that this was kind of a front for retiring-esque media management reasons, and indeed he continued to produce art. Others would say that these are weird ways to look at it either way, and that he was simply some guy who played chess and made art. Anyway, he made a famous chess problem.

The above linked excellent post on Tout-Fait, “The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal,” explores the background and analysis of this “problem” and ends with an unrelated(?) quote from Duchamp:

“There is no solution, because there is no problem.”

…There is sort of a problem, though, isn’t there? Or is there. I don’t know. Here, I had written an upsetting paragraph about where games are popularly situated in our miserable excuse for a society, and then I deleted it.

Maybe we can say not that there is a problem, but that there is a chess. I will leave it up to you and your brain tools, dear reader, to determine for yourself where to go with that.

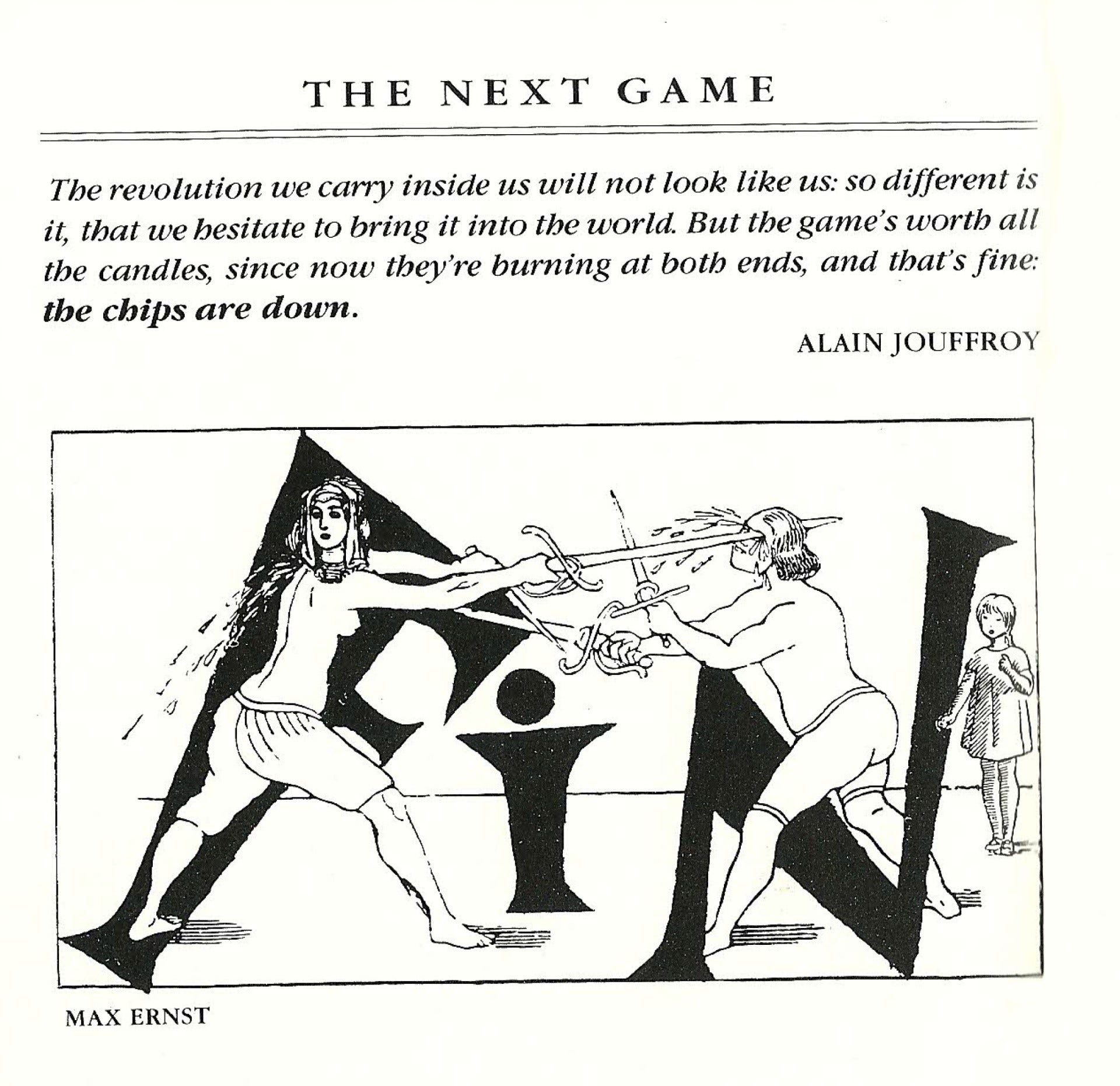

“The revolution we carry inside us will not look like us: so different is it, that we hesitate to bring it into the world. But the game’s worth all the candles, since now they’re burning at both ends, and that’s fine: the chips are down.” ―Alain Jouffroy