The available terminology for this category offers only very broad brushstrokes or else a here-and-there technical precision that excludes or compounds ridiculously in verbosity, so I’m just going to invent a more concise term. I am referring specifically to an extended family of games, commonly real-time computer simulations of fantastical physical combat, which attempt any degree of simulation of the material reality of swords as breakable and/or “realistically” maintenance-needing objects. (This fails to encompass role playing games that use number-crunching on paper or even similar types of virtual games that don’t rely on “video” or real-time simulated motion, per se. It also ignores other kinds of negligent sword conditions such as tarnish, blunting, etc. and other more or less identical simulations of breaking armor, sticks, farming implements, and so on.) Anyway, I’m going to call them Video Games with Breakable Swords, or VGBS. I’m not trying to establish something here. This is just for my purposes, below. It sounds normal and video gamesy enough, hopefully reads comfortably, and we can just pretend it covers all of the above.

SWORDS BROKEN

Why Is My Sword Breaking In the Damn Video Games (ft. The Green Knight)

This the third issue of “Swords Broken,” a series of blog posts about broken swords. The first post can be found here.

December 14th, 2024

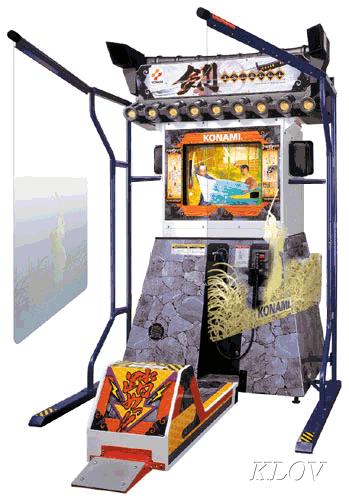

I remember sometime back in the early 2000’s, age 12 or 13, I was in a movie theater lobby and saw an arcade game that stopped me dead in my tracks. It had a controller shaped like a sword hilt attached by a cable to the cabinet and a frame of motion sensors surrounding where the player stands. “This is it,” I thought, adjusting my large eyeglasses designed for a cartoon turtle, “Video game sword... They finally did it.” I put all the money to my name into the machine and picked up the controller, ready to meet destiny.

The sensation that sticks with me to this day is the weight of that very heavy cable pulling down from the bottom of the controller-hilt in my hands, inhibiting natural movements of my tiny arms. It was kind of the opposite of a sword, like a practical joke from a bad dream; there’s no blade where a blade should be, and all the weight is flopping around on the other end of the handle. Maybe I should have been prepared for the experience by this immediately obvious irony, that there was no sword at all. Maybe I wasn’t tall enough for the sensors, or maybe I was just not very good at video games. If I were an adult with a better understanding of the limitations of the technology, I probably would have had a good enough time with it. I was hugely let down, to say the least. It was not so good. Jaded, I entered the mindset of the Spider-Man 2 jazz club Peter Parker. By the end of the decade, I was slagging off those Wii Sports Resort sword games. 2006’s Twilight Princess did a bit of motion-controlled sword, or so I hear (never played it), and I recall being pretty psyched for Red Steel 2 before the memory of my arcade trauma turned me back toward a detached skepticism (never played that one either). Then, of course, there was Fruit Ninja. These were dark times.

Above: the bastard machine that wronged me. (Source: forums.arcade-museum.com)

Before moving on to what I assumed would be more challenging subjects in this series of blog posts―Tolkien, real history, myths and folklore, etc.―I thought I could make a quick stop somewhere to blab about funny video game stuff. I ended up having an extremely difficult time organizing my thoughts into anything coherent and worthwhile. It might be clear to you, already, why this is the case. There has been, in the last 10+ years, a certain reactionary movement organized around perceived grievances by gamers dissatisfied with their entitlement to simulations of violence not meeting shallow expectations, and the baggage and real damage thereof has evolved into a cancerous form of politics that is still winning ground.

So, uh, I just needed to acknowledge that, and to begin with the clarification that the point of making of a video game is not to create a duplicate experience of reality or, worse, to a create an experience of a prohibited reality (or, even worse, to create a duplicate of reality in which to experience prohibited actions), but rather to make a game or an experience that cannot be had otherwise in any other reality. The worst excesses of this confusion, now history-defining in their scope, are the crowning achievement of the prototypical Guy Online Who Has Some Complaints About Swords In Video Games, and that connotation may be inescapable at this point. My intention is not to go all “cinema sins” on gamer swords, so to speak. It may at first sound that way, and there is, in fact, some cinema in here (The Green Knight, 2021) as a sort of counterpoint and honorary mention. I believe there is something worth talking about beyond the backseat game development and myopic nitpicking, and I believe it may even present a picture of escape from the above described mindset for those wielders of imaginary swords. Getting to it, unfortunately, will first require a review of some of those quirks of simulated materiality found in the format of visually interactive computer thingies more commonly known as “video games.”

• • •

What we are actually here to talk about is broken swords. In video games with breakable swords (we call ’em VGBS), for example your Dark Souls, your elder’s Scrolls, the Minecrafts, recent Zeldoids, etc. ad infinitum, we see different methods of simulating what is commonly known as “durability” or perhaps more aptly “condition” of tools like swords. This may consist of a rating on a continuous scale from a perfectly 100% full bar to a broken, empty bar, or it may be an incremental status of “normal,” “damaged,” and finally “broken” (like in Caves of Qud, sort of). Damage or breakage of swords can be redressed via “repair” of the weapon executed by the player character or by visiting a swordsmith, a vendor of tools or teacher of smithing skills, or some kind of shrine, I don’t know, some kind of elf or something.

THE BOY HAS TOO MANY SWORDS

I first started questioning this conventional approach to VGBS while playing The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, wherein the breaking of swords is taken to such a ridiculous extreme that it’s impossible to ignore. In the role of the hero, a handsome goblin boy named Zelda, the player ends up essentially carrying around a huge bag of expendable weapons that rapidly wear out and break, becoming unusable (actually bursting into shards and vanishing). Weapons cannot be repaired; they simply break and must be replaced with something else. This system was somehow completely functionally sustainable and yet utterly ludicrous, not just from a gameplay standpoint (which was contentious) but also as it pertains to the core premise of the game: that the hero is super good at fighting. He just doesn’t seem to know how to use a sword right. Maybe the fighting is too intense, the enemies too great, for a well-wielded blade to do any better than if he were to use it like a ballistic impact weapon.

Source: YouTube, Jack And Kayak

There is no evidence that he ever uses a sword like a sword. The boy drags around an impossible quantity of armaments only to grind them all away into iron filings, dust in the wind, like so much shrapnel in a brute force assault waged against enemies as small as slime or birds and as great as giants and demons. Iconic sword hero. Does not care about swords. Swords are debris to him. Actually, the more I talk about this, the better it sounds.

But the whole point of a sword breaking in a VGBS, aside from just adding complexity or difficulty to the game, would seemingly, at least superficially, be to bring the pretend sword closer to something more “real” and thus have the player connect to the simulated experience that much more immersively. If you have to care for your weapon, it becomes your weapon, or so the thinking goes. You care for it, and you care about it. This is where I believe BOTW and most VGBS shoot themselves in the foot. There’s nothing “real” about burning through swords like tissues, and there’s certainly nothing personal about it. It enforces and sometimes finalizes the disconnect between you and the virtual object.

The sequel, Tears of the Kingdom, was lauded (complicatedly) as having fixed this issue with the item-combining “fusion” ability, making it even more wacky and fun to break stuff and encouraging you to create and iterate your way through a variety of ridiculous, improvised bludgeons, absurdly long polearms, and grotesque picks and mauls ...which might be a better game, but it ain’t really swords. I do appreciate how hard they leaned into this. One of the first things you learn about the world of the second game since the events of the first is that all the iron weapons have rusted, the whole armory of a kingdom lying in broken decay. I don’t remember if this is explained, probably because I just liked it on my own terms and wasn’t paying attention. I didn’t finish the game. Also the Master Sword breaks. There’s a sword called the Master Sword, which is a really good sword, and it breaks too. I sort of remember that part. I hope it doesn’t deserve its own post.

Above: Scene from the opening of Tears of the Kingdom, where Ganon?...dorf?.. guy breaks the Master Sword with his goo arm

DOCTOR, MY SWORD... IT’S BROKEN IN TWAIN

If we focus in on the idea of “caring for your weapon” in a VGBS, we arrive at something exemplified by The Elder Scrolls series of games. In such games, you may have a sword (perhaps many swords, but you have a favorite, probably). You use the sword. The condition of the sword is reduced from usage. If this goes on too long without attention, your sword will break. You take the sword to the smith and pay away some of the spoils of your adventuring due naturally to the care of the sword, or maybe you spend some time to acquire the tools and skills to do it yourself. If you are neglectful, and the sword breaks, it can still be repaired, but for a higher cost.

Above: Some kind of elf man in TES4: Skyrim. He is making a lot of hot swords.

In TES3: Morrowind (2002), for example, the player learns to care for weapons with a toolset consisting of a hammer or tongs (not a hammer and tongs, but a hammer or tongs). No forge is required, no whetstone, no oils. Nevertheless, this is better than nothing, right? You must take care of your sword, and the tools are the functional signifier of that. But what we are actually supposed to imagine is happening here becomes further complicated by the outcomes of negligence. If the condition of your sword drops to zero, it cannot be used. It’s just... “broken.” It doesn’t do anything anymore until it is repaired, not even against a worm or a dishonest mud salesman.

Isn’t this like that Mitch Hedberg joke about escalators? A broken sword is never really broken, it just becomes a dagger (shout-out to Dark Souls, by the way, which includes a broken sword as a distinct weapon). At minimum, a broken sword is an iron club. It could even be a decent parrying dagger, a thrown distraction, or a valuable quantity of metal, or... no, no, in the VGBS, your sword is broken, and it’s garbage now.

Above: Broken Straight Sword from Dark Souls (Source: darksouls.wiki.fextralife.com)

In the VGBS, all sword use tends to damage the weapon equally and at a continuous rate. There is no convenient way I have seen to simulate correct execution of a cut or thrust with consideration of anatomy, of blade orientation, or of a strike against armor or a wall causing damage to the blade. I’m imagining something like a golf-stroke meter, which would be a bit tedious to apply to every slow-motion strike. These things are too physically granular to put into a game that needs to spend its resources on other, more gamerly things.

The same could be said about the actual quality of the “break” of a video game sword, which, to be clear, is very different from the reality of damage and disrepair of bladed weapons. In reality, swords can sort of “break” and then be repaired only in ways secondary to the blade of the sword―like, say, damage to some component of the guard, handle, or pommel―but if we mean the blade, the part of the weapon that must cut and parry, actual breakage is not reasonably treated with repair, and damage occurs in ways that are mostly not qualifiable as a “break.”

Frictional blunting or tarnish reduces sharpness. Bends, dents, twists, or chips in the blade also impair or interrupt proper cutting movement and introduce faults where breaks are more likely to happen. All of these except the last can be addressed by what you might call “repair,” i.e. blade maintenance between bouts of use. However, if a blade is chipped or truly broken in two or more pieces, if the integrity of the blade as a single, whole, forged piece of steel has been actually interrupted, then there is not really anything that can be done to repair it to the full quality of what was instantiated at the moment of forging. The sword could be reforged, worked as a piece of metal into a blade, but it would, at that point, essentially be a new sword.

Above: This is a gif I found of a sword from a Roblox game. Pretty cool gif. Roblox is a horrifyingly unmoderated game that exists to extract money from children. (Source: roblox-site-76.fandom.com)

BURNING ALL THE CARBON ON THE PLANET TO SIMULATE ONE SWORD

It’s not just the care and proper use of swords or the treatment of broken blades that’s impossible to simulate in video games. It’s swords as a whole thing. The real sword is kind of indescribable and unexperiencable except as itself; it exists at a strange intersection of precision and tenuous fragility characteristic of human life.

To that point, let’s briefly contrast swords with other video game items such as “gun” and “bomb.” The physical mechanisms and manual operation of the real versions of these things certainly have their own complexities not easily translatable into virtual simulations (indeed, all games that feature them require huge shortcuts and omissions to make them work in the game at all), but the essential experience of them happens faster than we are able to see or think and is thus much simpler to simulate convincingly. You point the gun at something, and if you pointed it right, the bullet hits the target. The bomb blows up, and if you were too close to it, you get hurt. When it comes to a sword however―or, better, two swords in opposition―we’re talking about human minds and arms controlling the angulation and pressures of blades interacting in 3D space, in real time, using 64+ articulating bones of the shoulder, arm, and hand for any given action, throwing your body weight around, minutely adjusting distance, doing all kinds of things with geometry and time and momentum that Zelda has never even heard of, yet are intuitively familiar to us on some level.

All of this in combination with the mundane nuances of using and caring for a blade amounts to something that can’t really be replicated in a real-time virtual experience or would have to be somewhat dice-rolly in approximation.

Maybe a better comparison, a middle ground between guns and swords, is... cars. There are a lot of cars in video games. We have reached a point where the physics of racing around in cars can be very realistically simulated. The damage to a car’s internal workings can even be taken into account, to an extent. But there are things that aren’t always completely covered in the simulation, like the effects of different terrain on traction, the weight distribution of passengers and bags of swords in the trunk, the mechanical impairment of an axel getting slightly bent when you ran over a parking meter to collect 200 elf coins. But none of this matters. Cars are done in a specific way in games that captures a desired experience without being tied down to strict reality. And people love it. They love those cars.

I don’t believe that swords could ever be simulated to that degree of complexity, but I think that’s a good thing. If they were easy to simulate, they wouldn’t be the mystical, reality-sundering things of legend that we see them as. They would be nasty or tedious or both. VGBS want it both ways, and in trying to pin down the “reality” of swords in a simulation, the harder they try, the more they misspend their way through limited time and resources into a weightless, flailing, dull thing. Or a huge bag of broken swords.

Vague sword stuff, however, generally works good enough in games because actual swords remain a total mystery to most people in actual, real life (again, a good thing). At its best, this kind of thing stays mysterious, simplistic, subjective. Less questing and battle, more sparring and dueling. Nidhogg is good. Bushido Blade II was good. Hellish Quart looks good (I haven’t played it). That’s all I can think of. These are sword-like experiences that do an excellent job with specific elements of the sword thing, giving you the basics of something in order to let you play around and tap into something bigger. Worrying about the condition of a blade is not fun or magical.

SURRENDERING TO THE PROCESS

That’s the overexplained crux of video games 101, the understanding that their most sublime purpose is to convey a certain experience or allow experimentation that isn’t necessarily much to do with the more superficially immediate setting, events, or elfs of the game, and thus the most fruitful work is never going to come from a 1:1 perfect simulation, which is impossible and redundant anyway.

I saw this Willem Dafoe quote a few days ago about an analogous aspect of film:

“The Art of Surrender” ― Willem Dafoe in Conversation, Vulture, December 5th, 2024

Vulture: Does the word “realism” have any meaning to you as an actor?

Dafoe: No. When you say “realism,” I think of naturalism, and I think about natural acting. And when I think about natural acting, I think about natural behavior. And I think sometimes that destroys movies, you know? Because we don’t just want to see imitations of life. We want to see something that is beyond that. Cinema is not just about telling stories. Everybody clings to this. Telling stories, telling stories, telling stories! It’s about light. It’s about space. It’s about tone. It’s about color. It’s about people having experiences in front of you, where, if it’s transparent enough, they can experience it with you. You become them. They become you. That’s the communion. That’s the experience.

Video games (bear with me here) are not movies. But we are sort of the actors in them. That’s kind of what playing is. It’s a different route to a similar end; in both cases, you don’t entirely get to choose your path. Later in the same interview, they talk a bit about surrender.

Vulture: You’re telling me you’ve never had an experience where you were being strongly pushed to give a particular type of performance, and you drew a line in the sand and said, “Nope. I’m doing this other thing”?

Dafoe: Never. I don’t think ever. I’ve been annoyed sometimes when someone pushes me in a direction I don’t feel comfortable with. But―not to make it sound like I don’t have a will―I generally try to find a different way to satisfy them, one that also satisfies me. Then I get there and I try to give myself over to the actions. And something happens. That’s the beautiful thing about making movies. They have their own life. They come alive or they die, but they shift. And you have to be sensitive to that.

Vulture: You surrender to the process.

Dafoe:Yes. I think it’s the only way. Surrender means forgetting yourself and trying to see another point of view, or trying to see another way, or trying to have different impulses and feelings and experiences.

In The Green Knight, there’s a scene where the not-yet-sir Gawain is captured by a small group of bandits. They end up running off with his horse while Gawain is bound on the forest floor. He struggles to squirm his way over to his sword and cut the ropes from his arms. Then he runs off, calling the name of his horse Gringelot, who’s long gone in an uncertain direction. In embarrassingly typical fashion, I was fatally distracted by one thing between this scene and the next, which is that Gawain does not pick up his sword. He leaves it on the ground and runs off into the dark woods. The idea that he would leave behind his only remaining weapon, a thing of great value which he’s just used to save himself, and race toward a group of armed bandits ostensibly in order to get his horse back, was a bit of a leap for me. It’s not so much that I demand absolute “realism” in my media, but rather that certain things are notably difficult to ignore and thus distracting. Or, that’s what I would say if I had to defend myself on this hill. (There are other more interesting things to discuss in critique of this film, but here we are on the sword blog.)

I realize, now, a few things. First, Gawain is incompetent, or at least not so heroic. That’s part of the story from the very first scene. Second, leaving behind his sword reads nicely, I think, as entering a different phase of his quest. It’s not really about the sword anymore. His whole story with fate and the Green Knight is one of surrender; he believes he is probably going off to kneel and accept his death. He’s learning something about the Green.

Later, there’s the following incredible monologue:

LADY: Why is he green, do you think?

GAWAIN: The knight?

LADY: Yes. Was he born that way?

LORD: Perhaps it is the color of his blood when he blushes.

LADY: But why green? Why not blue or red?

GAWAIN: Because he is not of this earth.

LADY: But green is the color of earth, of living things, of life.

GAWAIN: And of rot.

LADY: Yes! Yes...

We deck our halls with it and dye our linens, but should it come creeping up the cobbles, we scrub it out, fast as we can.

When it blooms beneath our skin, we bleed it out.

And when we, together all, find that our reach has exceeded our grasp, we cut it down, we stamp it out, we spread ourselves atop it and smother it beneath our bellies, but it comes back.

It does not dally, nor does it wait to plot or conspire.

Pull it out by the roots one day, and the next, there it is, creeping in around the edges.

Whilst we’re off looking for red, in comes green.

Red is the color of lust, but green is what lust leaves behind, in heart, in womb.

Green is what is left when ardor fades, when passion dies, when we die, too.

When you go, your footprints will fill with grass. Moss shall cover your tombstone, and as the sun rises, green shall spread over all, in all its shades and hues.

This verdigris will overtake your swords and your coins and your battlements and, try as you might, all you hold dear will succumb to it.

Your skin, your bones. Your virtue.

...the last lines now have me thinking this post should have been primarily about The Green Knight, regardless of its technically lacking in broken swords

Is there a lesson here for the VGBS? Maybe for a game with a linear story, but not so much for the systems-oriented games we’ve been discussing, that is to say games with broad customization of experience. Insofar as video games can trend towards power fantasy, yes, there must be something here, and that’s especially true for games where the player is allowed to make every last thing about their character just how they want, to break in anywhere on a whim, to experience every single thing possible. The top shelf video game of our time, the gamer’s game, seems pathologically trapped in a contradiction between service to the power fantasy and, on the other hand, an assumption of needing to provide little fixable broken sword moments for “immersion” and “player engagement.”

This was supposed to be a blog post, not an essay, and I don’t exactly know where I’m going with it. So, I guess rather trying to wrap things up neatly, I’ll just leave it here for you to figure out yourself. There are so many ways to do things. You can go on a quest by leaving your sword on the ground. You can turn a broken sword into a trowel, grow some potatoes, I dunno. Oh, to beat “swords into ploughshares,” lol, there’s already an expression for this. It’s from the freaking Bible.

Okay, bye. Seeya next time.