Art by Nora Krug (text removed)

Thinking Correctly and Frowning: On Timothy Snyder’s On Tyranny (Graphic Edition)

January 31st, 2025

Recently, for obvious reasons, I’ve been seeing a lot of this book shared around on the blue website (not that one, the other one, no, the other one). The book is On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century, by Timothy Snyder―the 2021 “graphic edition,” after the 2017 original. I first read it, lent to me, about three years ago. I am not happy with this book. I’m not a fan of tyranny either. What follows will hopefully be more than wild quibbling. I’m going to do my best to provide citations for where my views are coming from and to hopefully arrive at better ideas within the same currents the book explores. I guess what I’m doing here is hijacking.

Although I understand that they are my friends, it feels impossible right now to have productive dialogue with people addicted to this kind of commentary. Trying to get myself to even attempt to reach out feels like an unrealistic stretch over an unbridgeable gap in social reality. Not only that, but it’s years late and treated in all quarters as a treason or a poison or a sin. It sucks on an existential level and echoes the darkest moments of political failure preceding the rise of the greatest monster of the last century. But we have to at least keep trying to talk about it, trying to eventually inhabit something close to the same reality before we find ourselves undeniably in the worst possible one. This book concerns itself with that very eventuality, so here we are, let’s talk about it.

I haven’t read the original 2017 version or any of the primary sources, which may inform better arguments. Snyder is a legitimate historian and speaks the languages of the histories he studies. He surely has a more rigorous process and a deeper familiarity with the events he retells than I, some blog guy. Regardless, this edition is like, out there observably doing something in the flux, and it is not strictly a work of history. I want to talk about it on the level that it does what it’s doing, in your feed on your shelf, your friend’s shelf. I’m not going to make any claim that the specific facts he’s sharing are wrong―they might be, I wouldn’t know―but the lessons he would have us take from them are subjective. The book is, after all, ultimately presenting “twenty lessons,” and we would do well to note that historical lessons, if they were clear and constant and consistently followable, would surely have already led us to utopia. No, lessons are constantly proving or disproving themselves, both and neither, eternally smushing around in relation to the unexaminable, unscientific moment of causal ambiguity that is the present and the next thing looming around the corner. Sometimes they’re right, sometimes they’re right and then later wrong. They’re words we tell ourselves to steady our hand against the anxiety of uncertainty during times when we must make choices.

My take on this book, to be brief and uncharitable, is that it’s mostly anesthetic moral pablum phrased in that quintessentially MSNBC-commentator way to reassure the center-left that they’re doing all the correct things already and should stay the course and speak boldly and righteously via eloquent, noble, brand-approved mouthpieces from within their media bubble. Make no new choices. Never look outward, never change, never risk anything that puts friction on the surface of the bubble, never wonder if anything else is possible other than restoring yesterday’s business as usual, never suppose that those loud, uncouth new people who’ve taken very different lessons might see some version of a reality worthy of consideration.

Also, I don’t think we further left are immune to this kind of tunnel-vision. We only find out by engaging. Let’s go:

Prologue: “History and Tyranny”

The book starts, unsurprisingly, with an exceptionalist retelling of the supposed origins of America. “The American experiment,” begun by the Founding Fathers, is rooted in their philosophical contemplation of “the descent of ancient democracies and republics into oligarchy and empire.” I accept that this is true insofar as those ancient democracies even were democracies, insofar as our democracy is democracy, and for the fact the founders did consider it, but from the jump here it’s difficult for me to ignore that these men were themselves oligarchs―slaveholding economic elites conspiring to determine how the government works―and that they structured their democracy with certain rights only for certain people. Snyder himself points out the latter half of this problem, in his way, with the continuation that “Much of the succeeding political debate in the United States has concerned the problem of tyranny within American society: over slaves and women, for example.” The art on these pages shows a drawing of George Washington that’s been cut to pieces and taped back together, askew. His introduction of the political organization of America is not at all ignorant of its most overt problems at inception. My problem with it, however, is the implication that the founders were unique in dealing with these problems and the reverence for the untouchable, unquestionable thing that they created, an experiment with no end that mustn’t be replaced even when it has grown a terrible virus. We’ll come back to this whole “American experiment” thing later.

Snyder is a scholar of the 20th century and will have a lot to say about “the communists.” It’s just... it’s the damnedest thing, hearing anyone anywhere on the political spectrum say the words “The Communists.” It’s like when we talk of “Chinese food” or “content” or “AI.” An immediate signifier that we don’t know what we’re talking about, hopelessly cannot escape talking about a fake version of it. Can we be more specific? Will we ever make it to a point where the education exists to acknowledge the work such brevity is doing, let alone find a vocabulary that does better? Throughout this book, The Communists will be cited A) in the past tense, relevant only until the end of what was known as the Cold War, B) as representing and doing the thing of actual, achieved communism, legitimately, which is why they’re called Communists, plainly, and C) as being a monolithic whole, espousing something fixed called Communism and having no disputes with one another, which is why they’re The communists. Admittedly, these are ideas that even various stripes of self-proclaimed Communist might believe, in some way or another, which makes this all the more difficult to talk about, but in the case at hand it must be said: these are all facile, occluding things for a historian and supposed political theoretician to base arguments around. Getting into it here would be a whole other thing, and we will have to move past it, for now. I feel like Snyder must certainly know these things, as a historian of his focus, but the fact that he chooses to speak on the subject and the above subject of the founding of America in this way, in this mass/pop-accessible setting, it clearly sets out the function of this book as surface level, all talk, self-reinforcing mythmaking. He has no interest in helping people think seriously about why our lives are organized in the way that they are or the possibility of participating in deciding otherwise for ourselves. If he wanted to do that, he would. He has the theory at hand. I’m trying not to say that this is propaganda. I’m trying to be not too harsh, and to understand this thing for what it is and for its few merits. But it is disingenuous and boring to skip past such fundamental matters and speak to readers as if they’re incapable of even consciously examining different political realities―which they might be, so long as none of their teachers ever give them the chance. But I guess that’s the territory.

Strangely, he’s right about The Communists (or who he means to refer to there) “following supposedly fixed laws of history,” but there is an immediate and grating lack of self-awareness blooming here in the prologue―a commitment to this magic idea of the founders and their philosophies as having hit upon a permanent, ineffable, mystic truth at the core of what humans are, forever, and thus delineating the only historical antidote to fascism available to us. This antidote seems to mostly involve quiet observation and contemplation of the American flag, knowing passionately that a secret, promised salvation lies somewhere behind it, and if only we can be good enough, it will come out for us. Maybe after another 250 years.

While we’re on the subject of founding myths and philosophies, a quick aside about indigenous critique:

If you are familiar with the academic need for primary sources in understanding people and places in time, it’s a short leap to recognize that in many cases there may also have been other witnesses of the same events. In the case of the origins of America, we have the whole existence of the native people of the continent and their observations of colonists, communicating with them, trading, living alongside them all the while.

What little I know about this is all from David Graeber and David Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything, a fascinating book with an unfortunately overzealous name. One of the major cases that the authors make in the book is that the European enlightenment, and thus the political organization of the new American project, was informed or even entirely formed by the novelty of contact with indigenous thinkers, that various tales of dialogues with these people (like Kondiaronk, for instance) were not just exaggerated, patronizing, literary puppet acts for the intellectual amusement of interested Europeans, but actual criticisms and lessons being given by indigenous observers who understood the critique they were making and understood why their systems were preferable. The ideological-philosopical veins concerned, having to do with native ideas of power and peace and tyranny, are traceable in the extant literature, in the intellectual fashions of European enlightenment thinkers and the explicitly indigenous ways they were often framed and presented, through to the organization of the new government of the USA and to the now-claimed-to-be American values that they are today. The Dawn of Everything, if memory serves, even received contemporary indigenous critique from people who pointed out that their leading native thinkers had already been telling this story for a very long time. These are valuable perspectives from fundamentally different cultural lenses and thus useful to breaking us out of the kind of solipsistic America-is-America-is-America spiral of mystery that we enter via the incantations backing up the 20 Lessons in Snyder’s approach.

1. “Do not obey in advance.”

⚠︎⯑︎☺︎🕬︎ ✨︎ Hi, sorry, we need to immediately run screaming all the way over to Lesson 19, “Be a patriot,” where Timothy finger-wags at draft-dodgers of the Vietnam War. Think about that. It’s the most obeying-in-advance thing I can conceive of; we don’t even have an active draft in the US currently, and he’s telling us not to dodge it, to obey and go to war when told. I’m not even mad that he contradicts himself. I’m sort of speechless, I don’t know what to do with this.

The choice to begin with this idea seems laser-targeted for maximal damage to my brain and is more or less the reason I’m writing this thing of dubious usefulness. This will be the longest section for me to review. It will give an overview of my whole confusion about the book; the rest will elaborate and nitpick some but mostly rapidly devolve into erratic and embarrassing jottings as I lose my grip on what I’m doing here. Anyway... “Do not obey in advance.” The phrasing of what he’s trying to get at here is, I have to say, poetic. It gestures at the kind of twisted eternal mystery of people that I continue to harangue myself over with things like what I’m doing here right now. But when I first read this chapter, I was completely baffled by what Snyder could ever have meant to say. Now, having read a bit about his current speaking on this point, I think I get it.

In an interview in early 2024, Snyder pointed out that NBC’s hiring of former RNC committee chair Ronna McDaniel was illustrative of this trend toward appeasing authoritarians. He’s right about that. We see this every day in 2025 from news outlets mincing words to medical institutions abandoning trans people, private companies firing marginalized employees over new federal policy, and so on. It’s a point about institutions, I guess. Institutions are run by people and have people at the top making big decisions, but they are institutions, and they function in a specific way. We’ll talk more about them in the next lesson. In the first lesson of his book, however, he tries to make this observation about “anticipatory obedience” into advice on a personal level for the reader facing fascism, posed as a thing with everyday application for people in communities, groups of people without institutional functions. It may have such an application, to an extent, but I think his case studies miss the mark and hit something stupider.

Snyder describes scenes of people, civilians in pre-/Nazi Germany and Austria, participating in antisemitic persecutions. He identifies this as the same kind of “anticipatory obedience.” This was confusing to me on instinct, because these people, at least the ones he talks about, weren’t seeming to act out of obedience to any command or threat and didn’t seem to be anticipating anything. The antisemitism was already out there in the open air. You could say that they anticipated what they might gain in reward, but this wouldn’t be the dynamic Snyder is describing. To put it simply, it looks to me like Nazis eagerly participating in being Nazis and loving it. No one had to command them to obey, because they were all doing it together. That’s what actualized Nazism into a reality beyond a set of ideas on paper and radio. I’m not saying that there weren’t some people with a stronger conscience who went along with things instead out of anticipatory obedience, out of fear of standing out and being targeted or punished during or after the rise of the regime, but Snyder doesn’t get into their situation and overall employs the advice “do not obey in advance” as some kind of spell-breaking magic phrase that everyday fascists only had to understand and resolve themselves to, and then they could have found the inner strength to decide not to do Nazism. As for his implicit meaning for the present, it’s both more and less believable for me to try and understand that we who are already inclined not to obey the fascists, having also read his book, can now make extra sure not to and also somehow project that into the world around us. I’m not sure it works that way, but it’s maybe a thing worth contemplating.

However, and this is a huge however, as we have now directly observed over roughly the past decade, the people actively doing the fascism already believe that they are refusing to obey. They believe very strongly, with what I’m sure feels like a pretty convincing mimicry of bravery, that they are disobeying the supposed liberal-commie-criminal-satanic overlords of the deep state. If we are supposed to teach them not to obey, in advance or whenever, I would imagine that there must be some very different way of achieving that than by simply saying “hey don’t.”

Extra confusingly, in the same section, he talks about the SS devising elements of the Holocaust in “anticipatory obedience.” The SS? The highly indoctrinated elite murderers of Nazism? The most Nazi of the Nazis? They weren’t obeying, Timothy! They were just doing what they do! They specifically joined up to do that, didn’t they? Are you telling me someone should have told the SS not to obey Hitler, their boss who is the reason they exist? I said I was going to try to be nice writing this, but I don’t know what the hell he’s trying to say to me here, or to who, or for what circumstance.

It would have been very interesting to talk about those other people we know must have existed, who I’m sure Snyder knows about in historical detail (because I think we meet them later in the book), who wanted to give aid to the persecuted or to resist bowing under pressure to conform amid a rising tide of fascism. People who, in fear, either did or didn’t act. This would be a way to actually talk about resistance. Instead, the lesson seems to be all about thinking correctly and frowning from an omniscient position of hindsight.

We are up against a mob of people damaged so conveniently as to be truly willing to acutely disobey (even if they are mistaken and actually obeying a greater, worse force, it’s undeniable that they have been able to disobey the state on a mass level of rapidly reorganizing new politics), while the dominant mode of the left―insofar as the left is a thing that can even be spoken of coherently―generally, is... this. Thinking correctly and frowning.

Why not just “Disobey” ...?

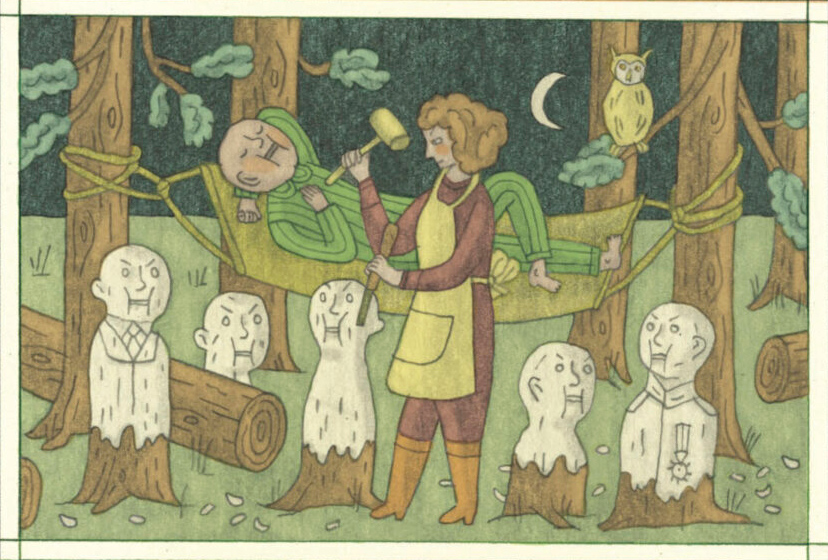

ART CHECK: Unfortunately, I like Nora Krug’s art for this book. I have some complaints later about things that I don’t think are working well in relation to the points Snyder tries to make, but overall it’s very effective. Some of the chapter title scenes are downright magical, really enjoyable to look at. If I may, though, toward the whole thrust of this review, I would like to suggest that magical-feeling, ambiguous scenes might actually be a problem in this particular case. The way they enhance Snyder’s vague, palliative approach to this subject creates a sort of mysticism. It feels enlightening to look at these pictures. Pictures are great at doing that. I think these probably could have been more enlightening on their own.

Next, Snyder talks about the Milgram experiments. Holy hell, he’s got my number. This is a huge pet peeve of mine. I’ve written about it before, in a silly little Cohost post. Read that, actually, if you want my whole take on the subject. In brief, the Milgram obedience experiments were a series of psychological experiments conducted at Yale University beginning in 1961 (and later replicated elsewhere in the world) wherein volunteer participants were led to believe that they were administering electric shocks to other volunteers in a staged, unrelated study on learning. They were led to believe the actor pretending to be shocked was the one being studied, when in fact they, the ones pushing the shock button, were the subjects of the experiment. The results were that a lot of people pushed the pain button a lot. In Snyder’s summation:

“Milgram grasped that people are remarkably receptive to new rules in a new setting. They are surprisingly willing to harm and kill others in the service of some new purpose if they are so instructed by a new authority.”

To thread this back to the prologue and to return for a second to beating a drum I’ll be beating for the next N,000 words, people are also very receptive to following rules in the old setting, to harming others as instructed by the good ol’ authority, which is why we continue to live in whatever world we live in. But Snyder repeatedly tells on himself by applying his worry only to obedience to new authority, to the rising tyrannical regime. We are comforted by our neglecting to wonder about our obedience to what’s currently humming along fine, what serves us well enough while for centuries having been a tyranny to millions of others now voiceless or vanquished. That’s just the sacred “American experiment.” And we’re surely not going to allow the hypothesis that this experiment may have always been leading this way.

My main gripe here, though, is that I can’t for the life of me ascertain what we are supposed to take from this story within the frame of “Do not obey in advance.” That there’s some spooky psychological force compelling us to obey new authority, so... don’t? Everyone can simply read this book or hear about the Milgram experiment and then they’re cured of it? “People can tell you what to do, so don’t let people tell you what to do?” Is this actionable advice? I don’t think so, and I think I’m not the only one.

Author Gina Perry breaks down the specific parameters and methods of the Milgram obedience experiments in her book Behind the Shock Machine: The Untold Story of the Notorious Milgram Psychology Experiments, which I confess I haven’t read. Around 2012, and for some years after the publication of the book, Perry summarized her case in a series of interviews, and the Milgram experiments had a brief, renewed moment in various pop-sci media outlets, which is where I encountered it. Perry is critical of the standard interpretation of the experiments and outlines distinctions between the data and the story that is told about them.

For example, well, let me just quote my own thing so I’m not self-plagiarizing: “First of all, as Perry and countless others continue to point out in vain, it is not exactly true that the oft-cited number of 65% of the participants went ‘all the way’ (meaning they kept pushing the button they thought was electrocuting someone to maximum voltage, sometimes until the recorded person stopped pleading and went silent). In fact, 65% of participants in ONE of several iterations of the experiment went all the way. Many of the other iterations had much lower rates. Regardless, that is a scary number, so it’s the one people have talked about the most, and eventually it became ‘The’ experiment. You’ll now hear that this means that most people would participate in torturing or killing you if it was their job, or if there was social pressure to do so. ... The experiments as a whole, however, were conducted in different ways, with differing variables, and, necessarily, with different participants each time.”

What this showed, in the terms of the most annoyingly parsed experimental rigor available to us, was that people can be more or less susceptible to going cog mode depending on the circumstances (i.e the experimental conditions, variables which produce different results). This is a strong reason to be mindful of power and social organization, to organize your society anarchistically, and most importantly to the topic at hand, to cultivate psychological resistance skills now by questioning and resisting the current authority―because how else can we practice such skills? By imagining them, Snyder believes, either in an unspeakable future or in the remote and alien past. He connects these imaginaries to us in the present by speaking about them in mystical little quips like “do not obey in advance” that feel really good, and in feeling them strongly we imagine that they are efficacious, and that this is all we need to keep everything normal.

Normal, the baseline American status quo that we used to have, the best possible reality, a never-ending experiment with a conclusion that is itself. Here there are no ideas about how to change it and no ideas about how to prevent it from changing. Myth-o-logical.

He’s got a point here when it comes to institutions, though. Why do they keep doing that? Is there perhaps something wrong with the structure of the institutions? Or is―

2. “Defend institutions.”

If you want to defend an institution, probably an imperfect one, and see a role for yourself staunching those wounds, trying to build something better out of it, sure, go for it. We need that. But I’d like to return to something that I mentioned in the first lesson, when we looked briefly at the example of disobedience of right wing insurrectionists and their leaders’ lack of obedience to a political status quo. Similarly, on the subject of institutions, what we are facing currently is a situation where they are prepared to move and the center-left establishment is not. So they lose. This is not to say that there’s nothing in institutions. But when an institution has repeatedly and catastrophically failed you, perhaps it is better to know when to move on to something else.

When do you stop defending? When do you know the ship you’re on is sure to sink? Might you suddenly find yourself totally submerged underwater, a begrudging functionary of the insurgent force you thought you were defending against? Even before that turn, if your institutions have failed against rising fascism, if your institutions are the driving force protecting capital and white supremacy, taking us to war like clockwork, keeping the machinery of ecological ruination churning ahead to oblivion, what then? Are you already a functionary? Can you allow yourself to leave? What if the scientists told you that within your lifetime we’d reap what we’ve sown? Do we dedicate our whole lives to defending the institutions of power and just keep trying to change them from the inside to mitigate the harm? For how long? Can you live that way? Are you allowed to live? Will you allow yourself?

Snyder makes no attempt to grapple with these questions. He asks us to take institutions on faith. Maybe the original text does better, which would, again, only reinforce the utility of this edition as a piece of centrist mysticism for people who are not trusted to learn.

3. “Beware the one-party state.”

“The United States is also a one-party state but, with typical American extravagance, they have two of them.” ― Julius Nyerere

Need we say more? Well, let’s. My version of this lesson, and the lesson prescribed by millions of my friends throughout history, would be “Beware the state.” It’s simpler, snappier, I think.

These lessons so far all gesture toward after-the-fact ideals surmised to be still present, if besmirched, somewhere behind chaotic social phenomena which are totally out of the hands, out of reach, of individual everyday people who might read this thing to soothe their soul, and the refrain of “vote” and “run for office” really reinforces that. Those are actions one can take within an existing system. You can debate them on those terms, if you want. But when something new, something really new, is growing within or under or outside that system, irrespective of its votes and representatives, and you refuse to grow your own thing and move along with the times, you learn nothing.

Snyder talks about the Russian oligarchy and its role in degrading democracy around the world (never mind the now unredacted history of US meddling of exactly that type) and then notes that the US also has an oligarchy problem, but inscrutably blames its acceleration on “globalization increasing differences in wealth.” (Look, I am not smart about economy. Trying to understand this sentence makes me want to cry. It is a bit funny though, just a bit, that they made this damn book with all its magical and very accessible sayings and pictures yet couldn’t resist, couldn’t STOP the man from injecting unexplained pet theories like that into it. I feel like they’ve asked Tim to come tell school children about Nazis, he’s sitting on a stool in the story-time corner and offhand mentions “btw oligarchy in the US is actually only being exacerbated by differences in wealth due to globalization.” Okay. Okay, thank you sir.)

He concedes that ”much needs to be done to fix [our electoral system],” and he names a few issues. I personally think maybe it’s a question of scale. Country too damn big. Maybe. I dunno. I will point out, at minimum, that the question of scale is one pondered by all tendencies across the greater left, but I have never once heard a theory of anything from liberal thinkers that even hints at knowing the question exists. So, that’s not something we can table for discussion here. We are in The American Experiment and the results of said experiment can simply be dismissed and promptly shredded while we await better results.

Instead of truly acknowledging and accepting that we’re in just another experiment, as already claimed, and that experiments are experiments, after all, the vibe of our many Timothies is always one of perfectly-imperfectly striving toward perfection, but also don’t you dare try to change the conditions of the experiment, because it’s not over, it’ll never be over until utopia, the end we’ve pre-decided for the very scientific experiment. Do real science? Reexamine our scientific standards? Scary!!! No!!! Science ended in the enlightenment, and we are now faithfully stuck with the methodology developed during a time when we still sort of thought disease came from stinky smells.

ART CHECK: Pages 20 and 21 do a decent little bit with the hands thing, then on page 22 we plummet into Drumpf slop.

4. “Take responsibility for the face of the world.”

In the previous chapter, Snyder shared this sexy little thing from somewhere in the back of his brain:

“The hero of a David Lodge novel says that you don’t know, when you make love for the last time, that you are making love for the last time. Voting is like that.”

Here I was compelled to make a silly joke, low hanging fruit, really, that the same could be true of anything―picking up your child for the last time before they’ve outgrown it, the last chip in the bag that you didn’t realize was empty, the last poop you take in a house that later burns down, the last time you say “skibidi” before it exits the zeitgeist―and then I realized it’s not a joke. It’s perfectly indicative of the fixated mindset our Timothies have developed about voting. Everything is like voting! He repeats himself, now, in chapter four:

“The minor choices we make are themselves a kind of vote, making it more or less likely that free and fair elections are held in the future.”

He’s referring to things like erasing swastikas off walls, an advice which precedes the above line and begins the chapter. We should do these things, obviously. I do. But trying to reframe it as “like voting” verges on obsessive. Don’t get me wrong, I understand what he’s saying. Someone sharpie-voted Nazi on the bathroom wall, and you sharpie-voted no with a scribble; this way and that the winds of public opinion sway. It sort of makes sense. But voting is voting, and other things are other things. Not everything is voting! Please try to understand things in terms other than voting! You know, in case A CRITICAL VOTE IS LOST AND WE ALL HAVE TO RETHINK SOME THINGS.

He does have something different to say, though. He begins to describe an interesting perspective on symbols in relation to the Holocaust and then immediately overturns it with this line:

“You might one day be offered the opportunity to display symbols of loyalty. Make sure that such symbols include your fellow citizens rather than exclude them.”

...How does that work, exactly, in practice? Am I stupid? When has this ever happened with a newly introduced symbol of loyalty to a state, movement, or ideology? When and for what would this ever happen? What are you talking about, Tim? Maybe we make a symbol that represents how everything is like voting, thus encompassing everything and everyone? I’m going to stop talking about this before it gets really dark. It’s just ludicrous. Impossible. Not a thing.

I enjoyed the story from Václav Havel. It was interesting. I feel that anxiety, hauntingly, in the slogans of movements that I even support, or have supported. That’s part of why I’m not big on slogans and chants. However, I wish that Snyder’s use of the story didn’t end there, at an example of a communist slogan that is still earnestly in use today (though I accept that its function in society within Soviet states was necessarily different). I wonder what else we’re supposed to do beyond this sort of thought exercise from the annals of history. May we, perhaps, tear down some symbols of authority? Reject them, openly and together on the streets and in the halls of power, taking responsibility for the face of our world? The one we live in, this country, in this century. Couldn’t we talk about that?

I’m going to repeat myself so many times here, but I have to say it: The more obviously useful, less-mystified application of this lesson would be to apply it explicitly to symbols in use now in the dominant culture that we live in. Otherwise, what are we doing? Pretending. Imagining how we would act in some distant future or past, offloading it as a situation for The Communists to deal with, in their unique folly. Refusing to look at the reality of our present.

5. “Remember professional ethics.”

I don’t have much to say about this chapter. It’s fine, I guess. Reeeally couldn’t be more apparent that this book is not aimed at like, impoverished laborers. It’s exclusively for members or aspiring members of the professional‒managerial class, things to tell ourselves while we wait to see what happens. Again, like with the institutions bit and elsewhere, maybe it would be more useful to honestly examine things like bureaucratization, groupthink, and prefigured suitability to fascism of a given professional field as a case study. Instead, what we get is the recurring idea that everything is normal and fine until the fascists start to appear out of the ether.

As an aside, you can also opt to refuse professionalism and choose life. That doesn’t have anything to do with the necessity of ethics, though.

6. “Beware of paramilitaries.”

Agreed, 100%, like the police for example. Oh, and beware also the regular military, your country’s or my country’s especially, oof, anywhere in a 12,000 mile radius or even and especially from standing within the ranks. Just beware, man.

In all seriousness, in this chapter Timothy straight up says that the monopolization of the legitimate use of force is good(?) because it enables democracy. Here’s the actual quote:

“Most governments, most of the time, seek to monopolize violence. If only the government can legitimately use force, and this use is constrained by law, then the forms of politics that we take for granted become possible. It is impossible to carry out democratic elections, try cases at court, design and enforce laws, or indeed, manage any other quiet business of government when agencies beyond the state also have access to violence. For just this reason, people and parties who wish to undermine democracy and the rule of law create and fund violent organizations that involve themselves in politics.”

...I guess maybe I’ve begun to take for granted, by proximity to the people I associate with, that this assessment of the state and violence is not always a critique. I suppose he’s right* in what he actually says here about how things literally functionally work, and I know that by “agencies beyond the state” he means fascist paramilitaries, and obviously I agree about the threat on that front, but as usual he’s making sweeping, idealistic statements about a quippy version of the thing on the table which ends up precluding any form of empowerment that people might reasonably take up against such a threat. Further, what he seems to be outright saying here is that he really doesn’t have a plan for how to respond if the legitimate entitlement to violent force is entirely coopted by an insurgent authoritarian political movement. This tracks through the rest of the book, where he offers no guidance on the matter whatsoever.

*Actually, I’m not sure he is right that “most” governments “seek to” monopolize the legitimate use of violence. I was under the impression that the point of this concept was as a defining feature of a state’s state-ness, that the state isn’t a state until they have obtained it. I would also argue that it doesn’t become “impossible” to do a lot of those things, it’s just messier or taking place during a civil conflict. This is quibbling. It’s just that he keeps taking the goofiest and most magical approach to talking about these things.

My question on this chapter mainly is, “What if the normal U.S.A., which already has all the violence, uses it, uh, bad; what if it’s normal and it’s very, very bad...” but I know there isn’t really an answer to that question.

The chapter ends with a bit about how paramilitaries “first challenge the police and military, then penetrate the police and military, and finally transform the police and military.” This is stated very confidently, precisely, and linearly, and I’m pretty sure it cannot possibly be true that things happen in only this way. I’m thinking of “warrior” culture endemic in police training, the Punisher-type death’s head memetics of that sort of thing overall in police and military community and retirees, not to mention the situation with fascist paramilitaries known to be entering the US armed forces in order to get training. And surely more phenomena than I can list offhand. Just another little thing that makes me skeptical of the author’s authority on the subject. It’s just a little too confidently and all-knowingly stated, just, y’know, the magical thinking of this book istg. Anyway, moving on.

7. “Be reflective if you must be armed.”

What he’s saying here is true enough, but it turns out he’s speaking only to armed active service members of the military and the police. Again, (see last chapter) use of violence is never legitimate beyond the arms of the state. That’s out of the question.

He talks a bit about our country’s “evils of the past” (none in the recent present) and the use of riot police by authoritarian regimes (certainly doesn’t happen under regular Uncle Sam’s watch). It’s more playtime pretend thoughts for us to stuff in our ears.

Crucially swinging and missing, Snyder ends the chapter without any suggestions at all about how to be reflective while being armed. He says “be prepared to say no,” and that’s about it, no suggestions as to how to steel oneself to do that. He either doesn’t have any ideas (likely because he’s never been armed), or the editor for this edition doesn’t want you to know them. You can wait to get that in basic training, maggot. (You won’t get it, though.) Otherwise, please hope that the military is reflective as they’re deployed against upcoming protests.

8. “Stand out.”

I thought this sounded like a lesson I could get behind. Snyder briefly says some truths about American mythmaking which he has spent the rest of the book ignoring wherever convenient. Then he spends four pages pitching Winston Churchill as someone who stood out re: Britain’s involvement in WWII. It’s not nothing, but it doesn’t really feel like something with applicability to standing out in the way that most matters on a daily basis against the rise of fascism―it’s about declaring war. Maybe it can be taken as an abstract inspiration. Then, oh, we have a story about a young woman in occupied Warsaw. I’ll stop complaining and read that now.

It’s a good story. It’s about Teresa Prekerowa, who made many trips to bring food and medicine to the ghetto in Warsaw, to “Jews she knew and Jews she did not,” helped some of them escape, refusing to let them “slip away,” as others had, out of sight and out of mind.

This story reminds me a bit of Dean Spade’s Now Is the Time for ‘Nobodies’, which ironically characterizes this kind of action as the exact opposite, as being “nobody” instead of “standing out.” There is a lot to say here. I think that maybe this is everything, to me. The whole thing could be about this. There is so much more dialogue to be had, stories to tell, different perspectives on the world that inform the space of this lesson from people that our many Timothies would never dream of taking seriously.

In October of 2024, Snyder shared some follow-up on this text, applying it to the present. It’s not hard to point out that deputizing people in a mass-deportation force reeks of fascist paramilitary, or that Trump’s talk of “the enemy from within” is a fascist dogwhistle. On “Stand Out,” he said this:

“It’s very easy to drift along and you might be noticing that a lot of people are drifting now. If you want to stop the drift, you have to break it yourself, even if only in some small way, even just by smiling and contradicting someone, even if it just means not letting someone get away with some kind of bullying or belittling remark, even if it just means walking away from a conversation, even if it just means putting a yard sign up rather than not putting a yard sign up, a little bit of standing out is necessary to remain who you are...If we just drift, if we just do the easiest thing, then we will end up in an authoritarian place.”

I like that. It’s all the more mystifying to me, then, why he wrote this book which in most other lessons seems to be a handbook for how to drift along.

Weird aside: I wonder if maybe this ambiguity between what is and isn’t drifting while one keeps one’s head down and keeps a human heart beating, I wonder if this maybe opens up a crack to a larger space of exploration where we find that there are many ways not to drift along, and not all of them recognize each other, and all of them are, to some degree or another, simply drifting after all.

9. “Be kind to our language.”

“Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does,” the lesson begins. I agree, but, again, I just feel that there is so little self-examination where so much could be said. He literally recommends reading Harry Potter in this chapter.

I do think it’s important to read fiction, and I’m glad he insists on this. Can’t complain too much.

10. “Believe in truth.”

How is he able to so comprehensively explain the place of the “post-truth” moment in the historical arc of fascism and also not see that you can’t just say that and have people do it. Have we been paying attention to our helplessness in the crisis of reality unfolding over these past many years? What are we talking about here? Who is this for? Well, we already answered that.

Snyder shares an outline of the degradation of truth in fascist thinking as observed by Victor Klemperer. He fleshes these out with examples of the things Trump does and says, the things his followers believe, and the things Hitler’s followers believed. He doesn’t miss. But something about it rings a certain way in the context of this book... What I’m about to do feels almost nasty, but it must be done. I’m going to copy/paste Klemperer’s four modes without commentary:

The first mode is the open hostility to verifiable reality, which takes the form of presenting inventions and lies as if they were facts.

The second mode is shamanistic incantation.

The next mode is magical thinking, or the open embrace of contradiction.

The final mode is misplaced faith.

11. “Investigate.”

This one is the same as the previous lesson, here in the truth soup. It doesn’t work. You’re just gonna tell people to investigate? People investigate their way into QAnon.

Okay, so he’s getting into the lies people told themselves about Vietnam, mhm... interesting that he’s still gonna tell us not to dodge the draft later, but ok... what else we got... Russian money, bots and trolls... it was 2017, but people were told to investigate and they did and everything is fine now. Ok, sorry, I’m getting a grip. It’s fine. There’s some stuff here, there’s some points, it’s fine. I don’t want to get into it. Journalism.

12. “Make eye contact and small talk.”

Short chapter. All good. I feel like I’m alienated for a reason, but what he says here is true enough. Finally an appropriately smushy subject to apply his magical thinking to.

13. “Practice corporeal politics.”

[Redacted]

14. “Establish a private life.”

This chapter was a real trip. I promise I’m not exaggerating the contents and playing up my bafflement. It’s seriously very strange.

On first impression, I thought I was into whatever he was trying to say. I was waiting for the good stuff, ignoring the awkward phrasing. “Scrub your computer of malware on a regular basis” is not a sentence written by a guy who knows what he’s talking about. That’s just not how we say that. Or maybe his computer really is inundated with malware on a daily basis? “Remember that email is skywriting. Consider using alternate forms of the internet,” man, EXPLAIN YOURSELF. This could have been information! You wanted to share information here and then you just didn’t! Anyway that’s only the chapter title page.

Then he spends the whole chapter talking about ...something. What is he talking about? I can’t tell, because he’s one of those guys who will sometimes refuse to say the name Trump when he’s getting in his most patriotically strident stance. He’s obliquely describing the situation with the uhh leaked emails? What was that about again? ...the “email bomb?” What the hell is that. I don’t remember that one. Comey is here? Comey is here and it’s a human rights issue? That can’t be right. What is this? Ahh, it was the―okay, we’re going to talk sideways about Hillary’s emails and then the chapter ends. What did this have to do with my private life? What are we doing here? He’s making the case that some kind of normalization of the invasion of privacy around the emails thing was a huge blow to human rights. Nothing to say about all the ways the government already does similar or worse to private citizens on a mass scale. Again, the chapter is about Hillary’s emails. I just don’t see the need to be talking about this in 2025. It is amazing, the amount that this sort of thing features in this book that people on my timeline are currently boosting as if it contains a real game plan.

15. “Contribute to good causes.”

....... . .... charity ...... mm,m ....... “it’s gratifying” ...yes, yes

...damn... wish I had some money....

..

.......

M- may I?

...May I suggest: Mutual aid? Can we talk about that? No, ok

16. “Learn from peers in other countries.”

I understand the point of what he’s rhetorically doing here with the relative novelty of our situation, but, I’m sorry, “The present difficulties in the United States” ... “familiar to the rest of the world” ...this reads like something they’d say over the intercom on the Snowpiercer train. It’s embarrassing. There are ways to talk about this that don’t lean in to pretending that there’s just a little interruption in service to be corrected and things will return to normal, and normal is A-OK.

At some point in this chapter, Snyder goes ahead and mentions that institutions were powerless to stop Trump. No need to talk about why, though. Just an interesting thing to note.

Now we’re talking about Ukraine and Russia, pertinently, aaaaaand for some reason, you guessed it, Hillary Clinton. For the 2021 graphic edition, you’d think they would go with a more topical application of the things touched on here re: disinformation campaigns. Again, this had the opportunity to be real information with applicability to people’s real lives, but it’s not, it’s a fixation.

I do want to get my passport renewed. No idea about how to get anywhere with it. Really wish I had money.

17. “Listen for dangerous words.”

He’s right, here, about things I hope the adults in the room had all learned 20+ years ago. I understand that’s not a realistic hope, and that some readers weren’t born yet. I just keep wanting him to get to the good stuff. The 101 material has to go somewhere, I guess, and I can see how this approach seems like a good idea. He somehow keeps whiffing partway though each lesson, though. “It’s the government’s job to increase both freedom and security.” For who? Since when? No one says this. Hang on, did a government write this? Oh my god, they got Timothy... they secured Tim

18. “Be calm when the unthinkable arrives.”

Sorry, my mistake, he’s back. This chapter is all interesting information about “terror management.” I can’t fact check all the events described, but I’m glad to have re-read it and will hopefully retain it this time. Similar to “stand out” (or the story at the end of that chapter), I feel like this lesson could be more useful as a larger standalone piece. For some reason, I’m less conflicted with this one on the ironic futility of trying to deliver the message to those who most need to receive it and are thus most incapable of hearing it. I guess it’s because “don’t be tricked” is not actionable advice, while “watch out for xyz pattern of events and question them” is more actionable and conveniently feeds good sustenance to the conspiratorial mind that is so otherwise susceptible to poison. And this is pretty good info considering the target audience, the readership potential, comfortable progressives who feel intuitively like they understand they shouldn’t give over their rights to Hitler 2, but who might go ahead and do it for Hitler 2.5 if they get really scared of terrorists. The Ring doorbells beg to differ, though.

He really insists on referring to Trump obliquely as “an American candidate” or “the American president” even when it actively harms the readability of his writing and serves no purpose other than the silly, sanctimonious, pearl-clutching thing that it is. Also―and I really, really, am loathe to make this point, but I feel I have to―he has already recommended reading the last or latter Harry Potter books “as an account of tyranny and resistance.” One thing that comes to mind from those books as actually having some kind of utility is the idea of not being afraid to say the bad guy’s name. He hasn’t even taken one of the most basic lessons from the children’s book he’s recommending, let alone noticed that it was written by a fascist.

19. “Be a patriot.”

No.

“It is not patriotic to dodge the draft.”

I think most of them knew that, man.

This is the part we skipped ahead to in Lesson 1, Timothy’s obey-in advance-squared moment re: the draft. Literally sign this paper when you turn 18 that says you promise in advance to obey.

“It is not patriotic to avoid paying taxes.” Again, I know, and I would love not t― OHH MY GOD HE’S TALKING ABOUT TRUMP. He got me again! This mf... he got me again, he just can’t bring himself to say the name “Trump” when he’s getting all high on his own supply and he keeps taking me on these crazy rides... jfc, this book. He’s doing this at the expense of what is supposed to be the point of the book! I thought I was reading a supposed lesson about tyranny and it turns out he’s just complaining about some inconsequential Trump factoid. I don’t care that Trump dodged the draft. Of course he did. He is of the class that sends people off to die meaningless deaths in wars for gold and oil.

Okay, I guess I see how it would be relevant if I was patriotic. But he isn’t convincing me there either. He warns us against nationalism―go on―and then spins around and explains “a patriot, by contrast, wants the nation to live up to its ideals.” No one else says this, that there’s a clear distinction there, or that the two are mutually exclusive. You just made that up, man. I guarantee you that virtually all the people in this country who most passionately pronounce their patriotism want me and other unpatriotic types either run out or buried in a ditch. I think you know that as well as I do, but you’ve made me come here to debate you about Made Up Nonsense. How about this, “a patriot is an idealistic nationalist.”

20. “Be as courageous as you can.” [Picture of guy killing bees. Okay.]

I hope I will. I really hope we all will. I am sincerely grateful, dropping the sarcasm for a minute, for what bits of real information I got from your book that might help me be that way, and I’m not lying when I say I believe it might, overall, in all its mystification and magic speech, might help people who don’t know better, people who feel the magic, to be a little more courageous. That’s not nothing.

Epilogue: “History and Liberty”

- We have a few pages about “the politics of inevitability” that I personally didn’t need to hear at all, being very much not in that camp, but I guess someone still might’ve needed to hear it.

- Picture of Karl Marx with pink hair. Wow, owned.

- Obscure admonition not to use the word “neoliberalism”―?? “Some spoke critically of ‘neoliberalism,’ the sense that the idea of the free market has somehow crowded out all others. This was true enough, but the very use of the word was usually a kowtow before an unchangeable hegemony.” ...? I don’t know what the second half of that means. Uncle Timothy is doing the thing again where he starts saying his things. Can someone actually explain this to me? Who is this book FOR? Who are you talking to when you say things like that?

- Okay, so he’s just freestyling a whole theory of history here.

- Vague, pictorial acknowledgement of American genocide.

- America is “flawed.”

- **Maybe the next generation will do America right.** Probably not! Just based on the odds, experimentally speaking, given how it’s been going. Would be great though. We’ll see, I guess.

- Shakespeare quote. Poetically ends with “Nay, come, let’s go together,” which I have to mention is really just a sort of stage direction thing that the actors are saying when leaving the scene. Hamlet is literally talking about walking off stage. He’s not like rallying and speechifying, dramatically saying “let us-” you know what, nevermind.

In conclusion, please stop getting advice on political action from MSNBC people. They have failed over and over and over, entrancing themselves with the ritual of this failure and the jolt it provides for their grave-monument ideology. They do not understand the world, because they are afraid to. They are just another flavor of self-hypnotized American desperation. They have demonstrated this ad nauseam. Look around and see. The world right in front of you is more beautiful than America. You can be free. You can escape. Do a vandalism today. Thank you.

MEpilogue

I want to share my version of these lessons in the form of a bunch of search terms and half-formed thoughts. (These roughly correspond to each domain of Snyder’s lessons, but I do mean roughly, and of course I’m not opposed to all his lessons or the sentiments behind them.) These are by no means things that I practice perfectly, or some at all. They’re things that I feel have, via interest in them, helped me to escape from this book’s type of immediate need for answers looping back to existing powers. But many of these are things you can in fact do in the immediate present of your life. Vicky said it best:

“Quiet reminder that the people who told you mutual aid, affinity group based work, anti-electoralism and other anarchist/non-hierarchical methods ‘wouldn’t scale’ and are ‘utopian/idealistic’ have nothing to offer in this moment, while those methods are responding to epochal crises and disasters”

My list:

- “Become ungovernable”

- Destituent Power, “the power is not in the building” (I can’t remember where this second thing came from)

- Beware the state, beware parties, and never stop asking “what is the state” and “what is a party?” Any time someone is saying to you “I’m you,” or “You’re us,” or “We are all him/her/this candidate/that group,” be suspicious of their intentions.

- Reject labels, categorization, and unity built on self-excoriation. Honestly problematize ideological labels. Live in the world as you. Be a clown.

- Escape the “Non-Profit Industrial Complex.” Quit your job, play around. Don’t push papers and expect things to change. “Lying flat,” antiwork, “shut it down.” Ask yourself if you actually do live in a society or if that’s exactly what they took from you. *Tim Robinson voice “what did they do to us”*

- “Buy bolt cutters.” Try sabotage. Property damage wielded correctly is not violence. Things thought of as weapons can be potent nonviolent tools. Learn to defend yourself and your loved ones. Oppose and disrupt policing if possible.

- If you are drawn toward violence, whether righteous or in self-defense or however you see it, find and study privately a spiritual line of inquiry renouncing or at least complicating the applicability of violence. Without this, you may find yourself with no control.

- Be “Nobody,” dismantle whiteness within yourself and try to return to the community of the world.

- Be a surrealist.

- Be a surrealist.

- Practice knowing unknowing. Truth exists, but the core of truth is unknowable. Truth moves; move with it. “God is change.” Test your assumptions. Never decide that you have found the core of truth; you haven’t. Don’t follow people who think they know how history ends.

- Find your friends and do a crime. Build something. Grow something.

- “Behave as if you are already free.” Direct action, “riot is the new party,” jail support, mutual aid, mapping, be fungus, associate freely, speak your mind.

- Disengage, disengage, disengage, disengage. Laozi says: Not that, no not that either, no, not that. “Stay low, mysterious.” Do without doing. Be like water. Attack surveillance. Use obfuscation where useful. Stay illegible to power. Make it harder, wherever possible, for power to consistently and constantly reorient itself to you.

- “Solidarity, not Charity.” Engage with mutual aid wherever you can. It doesn’t have to be “a good one.” It doesn’t have to be big.

- Study and share. Rethink boundaries of space. Internationalism without vanguardism, without a program.

- [Redacted]

- “The Way is the dust of the Way”

- People live in places. We can do this without notions of patriotism, borders, or war. Anyone who tells you otherwise is lying to you. You live in a place. “Build soil.” Grow chestnut trees. Seed-bombing, permaculture, Earthseed, graffiti, loitering, squatting, skating.

- Blessed is the Flame

I wish I had something more to add, something better. If anything, writing all this and arriving here has reminded me that a focus on exhaustively arguing against nonsense tends to be a distraction from simply doing something good, which will speak for itself. I’ll try. I invite you to join me. ■